Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/WHRWB/RA/004

The Regarding Sick Child Care for Children and Their Parents

Abstract

Aim: We surveyed users of sick child care services about the benefits of and issues regarding such care, in order to obtain an insight into its practice.

Methods: The study subjects comprised a total of 144 parents whose children had used any of the 15 sick child care facilities in Prefecture A in 2015. These parents consented to participate in the study. Using a quantitative and qualitative method, we surveyed them about their usage of sick child care, care-related requests, as well as perceived benefits and difficulties.

Results: Sick child care was used mainly by children from either double-income nuclear families (n=123) or single-mother households (n=12) because of infectious diseases. The systems for reducing care fees were utilized by 58% of the single mothers. Subjects viewed the following factors as the benefits of sick child care: 1) a sense of ease achieved through appropriate and professional childcare, 2) being able to work free from anxiety, 3) a reduced burden on children and their normal development, and 4) child raising support for parents. On the basis of difficulties in utilizing sick child care, parents desired improvement in care services, such as an increase in the number of both care facilities and days such care is available, and the capacity to accept children.

Conclusions: The results of this study suggest that, to facilitate sick child care based on the needs of care service users, there is a need to increase the number of care facilities, and expand the capacity to accept children.

Introduction:

The Japanese government is adopting new systems for child rising in order to respond to changes in the child raising environment resulting from the expansion of women’s societal roles and the trend toward nuclear families [1]. These systems aim to provide a wide range of child raising support, including improvement in parents’ employment situation in a manner enabling them to manage work and child raising. In particular, as sick children may hinder their mothers from managing work and child raising, the government is promoting the systems for sick child care [2]. Sick child care is a form of nursing care provided temporarily for sick children when they cannot be cared for by their parents at home. In 2012, approximately 490,000 sick children used a combined total of 1,102 sick child care facilities as supporters of working mothers [3]. The role of sick child care is not only to fill in for working parents by looking after their sick children, but also to meet the children’s needs [4]. Patents are able to benefit from sick child care in terms of both work and child raising, and such care is also beneficial for their children [5,6]. Most of these parents view this type of care as helpful in child raising [6,7]. On the other hand, there have been reports on dissatisfaction with the sick child care systems and care fees, as well as on parents’ anxiety about infection [7-9].

Against this background, we surveyed users of sick child care about the benefits of and issues regarding such care in order to obtain an insight into its practice.

Methods

Study design: Mixed methods research: The study subjects comprised parents whose children had used any of the 15 sick child care facilities in Prefecture A between October and November 2015. These parents consented to participate in the study. In this prefecture, care fees are reduced for families receiving welfare support, those exempt from municipal tax, and those exempt from income taxes. It is possible for service users to utilize sick child care facilities located in municipalities other than their home municipality in accordance with the specified municipal agreement.

As the demographic variables of the subjects, we investigated their age, type of household, employment situation, and monthly household income. We did not survey their residential areas because many municipalities of the studied prefecture had only one sick child care facility. In addition, we investigated the subjects’ usage of sick child care (e.g., age and diseases of their children, as well as the costs of and reasons for using such services), annual number of times using care services, whether or not they had ever been unable to use sick child care, and actions taken in such circumstances. We used 15 items regarding the benefits of sick child care (assistance for work, child raising support, and benefits for children), and 14 items regarding care-related requests. Each of these items had 4 possible responses. Furthermore, the subjects were asked to freely write down their opinions and requests concerning sick child care.

We obtained written consent from the managers of the 15 above- mentioned nurseries. Staff members of these nurseries then distributed a form describing the study, questionnaire, and self-addressed envelopes to the subjects. A response to the questionnaire was interpreted as having consented to participate in the study. In addition, to calculate the response rate, we asked each investigated facility to count the number of questionnaires completed in the facility.

Missing quantitative values were handled according to each question item. Using SAS9.2, we performed exploratory factor analysis and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Subjects using and not using the systems for reducing care fees were classified based on their payment of these fees. For qualitative data analyses, the statements in the collected questionnaires were repeatedly reviewed, classified depending on their meaning, and encoded while maintaining the main points of these statements. The encoded data were labeled according to their similarities, based on which the data were divided into subcategories, categories, and core categories. To ensure data reliability, all analyses were performed by 4 researchers.

The study objective/methods and ethical considerations were explained to the above-mentioned managers in written and oral forms, as well as to the study subjects using a request form. The study was conducted with the approval of the ethical review board to which the investigators belonged (27-02).

Results

Subjects: We distributed a questionnaire to 345 individuals whose children had used any of the 15 nurseries for sick children in Prefecture A, and collected completed questionnaires from 144 of these parents (response rate: 41.74%). All collected questionnaires were analyzed.

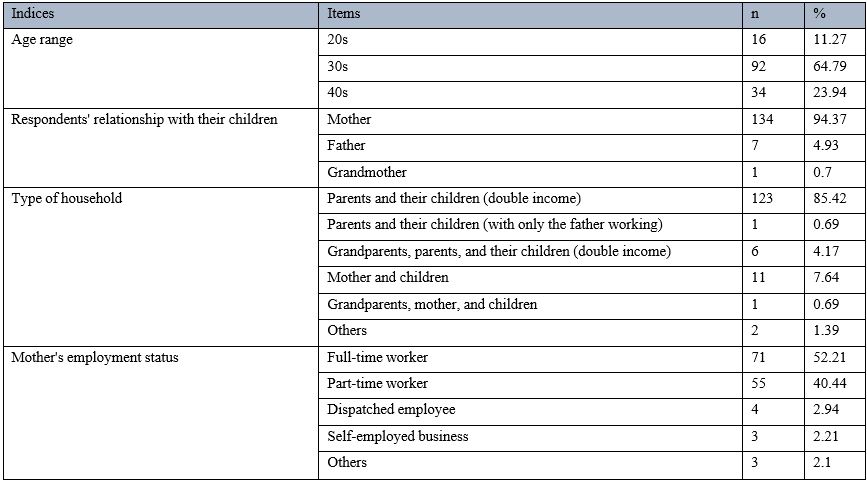

Quantitative data: Of all subjects, 134 were mothers; 92 and 34 were in their 30s and 40s, respectively (Table 1). Single mothers and those from double-income nuclear families numbered 12 (including 1 subject living with their parents) and 123, respectively. Subjects in full- and part-time positions numbered 71 and 55, respectively. The average daily working time was 7.96 hours (SD=1.69). In addition, 84 subjects worked on weekends, and 13 were night-time workers. The percentage of those whose monthly disposable income was less than 300,000 yen was significantly higher for single mothers (91.67% [n=11]) than people from double-income households (19.33% [n=23]) (P<0 n=7]) n=34])>

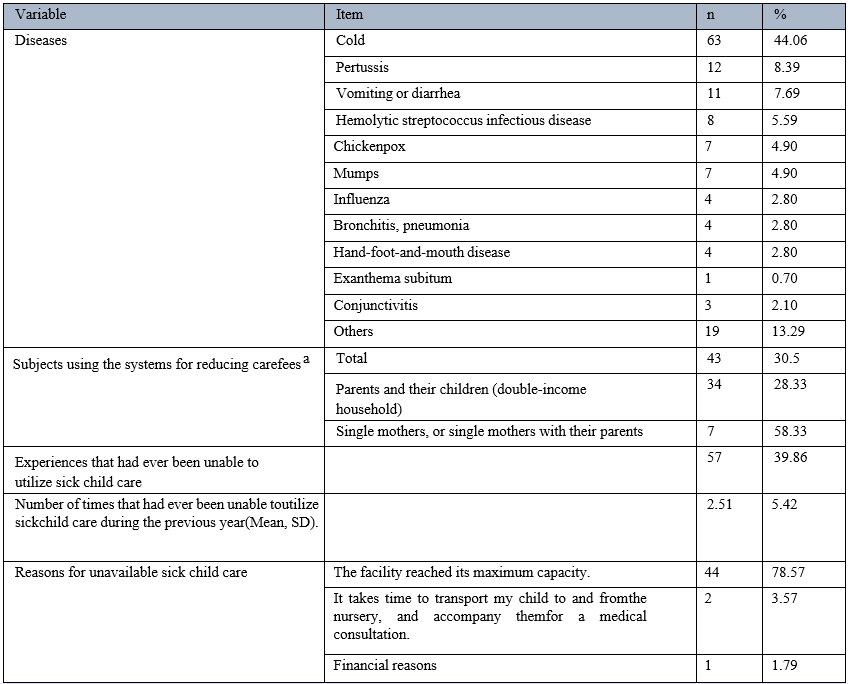

The average number of times using sick child care during the previous year was 4.42 (SD=4.34). Most recently, the average number of days using sick child care was 1.89 (SD=1.26), with the average number of hours using it per day being 8.09 (SD=1.32). The mean age of the children using care services was 3.07 years (SD=1.9). Among these children, 89 and 79 were male and female, respectively. In addition, 24 parents each placed 2 children in sick child care at any one time. Common diseases included a cold (n=63), pertussis (n=12), and vomiting or diarrhea (n=11). Most children had infectious diseases. The major reason for using sick child care was because of work (n=142). A total of 97 subjects arrived at their workplace late or had to leave early when using sick child care. Furthermore, 141 subjects desired to continue using such care ( Table-2).

During the previous year, 57 subjects had been unable to use sick child care at least once, with the average annual number of times it was unavailable being 2.51 (SD=5.42). The reasons for sick child care being unavailable were the maximum capacity of children had been reached (n=44), and financial issues (n=1). The actions taken when sick child care was unavailable included: 1) taking the day off from work (n=64 [48 mothers and 16 fathers]), 2) placing children in the care of their grandparents (n=15), and 3) making children stay at home alone (n=5).

A polychoric correlation matrix was created for the 15 items regarding the benefits of sick child care in order to facilitate the interpretation of these items. The data obtained from these items were then subjected to exploratory factor analysis (unweighted least squares, promax rotation) (Table 3), which led to the extraction of the following 3 factors: 1) a sense of ease achieved through using sick child care, 2) parents’ relief, and 3) benefits for children. Both the scale used and these 3 factors showed a polychoric ordinal alpha coefficient of ≥0.72, and an item-total correlation coefficient of ≥0.43, which established the scale’s reliability. Significant differences were noted in the scores for these 3 factors (P<0>

Discussion:

As was the case in previous studies [5,10], sick child care was used mainly by children from double-income nuclear families or single-mother households, primarily because of infectious diseases. Concerning the benefits of sick child care, the results of our study suggest that children can benefit from the expertise of such care, and parents can receive support for work and child raising when they“When I apply for care services the day before, I am often placed have no relative to look after their children. Parents viewed the sense of relief achieved by utilizing sick child care as the most beneficial factor of such care. Such a sense refers to feeling comfortable about the use of appropriate and professional childcare, and being able to work without worrying about the possibility of leaving the workplace early. In addition, parents considered sick child care to be helpful in that they do not have to rely on relatives, and that they do not need to look after their children by themselves. Furthermore, parents felt a sense of mental peace resulting from: 1) a reduced burden on sick children (no need to attend nursery school or receive a night-time medical consultation), 2) their normal development, and 3) their positive reactions to sick child care.

These positive views (regarding sick children’s early recovery and normal development, as well as child raising-related advice given to parents) are consistent with those reported in previous studies investigating care provided by nurses and nursery staff [4,11-14]. The results of these studies and the present study suggest that total care for sick children and child raising support for their parents become the basis for work support.

Some of the effective measures to facilitate sick child care are the systems for reducing care fees. In the present study, approximately 60% of the single mothers were using these systems, and only one subject had been unable to utilize sick child care for financial reasons. Sick children are a major risk factor not only for a reduced income, but also for dismissal from work [9].

In particular, such children are a serious issue for single mothers who are non-regular employees, or those with a low income [15]. In the present study, for more than 90% of the single mothers, the monthly disposable income was less than 300,000 yen, which is lower than that earned by households with children (330,000-375,000 yen, which is equivalent to an average annual income of 6.07 million yen) [16]. Therefore, for low-income parents, such as single mothers, the systems for reducing care fees help to ensure a stable income and job security.

Difficulties In and Requests Regarding the Use of Sick Child Care

During the previous year, approximately 40% of the subjects had been unable to use sick child care at least once and, for 80% of such individuals, the reason for unavailable care services was because of overcrowded facilities. In such circumstances, as was the case in previous studies [17,18], more than 80% of the mothers took the day off from work. Unavailable sick child care may become a serious problem for parents (e.g., single mothers) who have nobody to look after their children. When sick child care is inaccessible, parents usually have to choose one of the following 3 options: 1) take the day off from work, 2) leave their children at home alone, or 3) take them to their workplace.

The second option was noted in both the present study and previous studies despite a major risk imposed on children [9, 19]. In the present study, the average annual number of days using sick child care was 8.35 (1.89 days/time × 4.42 times/year). Although the annual number of days children aged 0-6 years are absent from nursery school ranges from 10 to 22 [19], parents are not able to take sufficient child care leave (up to 5 days each year when they have one preschool child) [20]. In the U.S. and U.K., it is prohibited to leave children with a health risk at home alone [21,22]; however, Japan does not have such a legal regulation. From the perspective of child safety, it is imperative to increase the capacity to accept children, number of care facilities, and upper age limit for using these facilities.

Approximately 70% of the subjects arrived at their workplace late or had to leave early when using sick child care. Such interference with work is caused by the time required to go to a sick child care facility, and short business hours at the facility. The business hours of sick child care facilities (10 hours) [23] are shorter than those of nursery schools (11.6 hours) [24]. Furthermore, some parents utilize sick child care facilities located far from home, for reasons such as a shortage of such facilities and an insufficient capacity to accept children. It is a heavy burden for sick children to go to a care facility far from home, and stay there for a long time. Moreover, when an individual uses a sick child care facility located in a different municipality without the specified agreement because of overcrowded care facilities in their home municipality, they will not be able to use the systems for reducing care fees.

For parents who suffered from various difficulties, the strongest desire was to increase the number of care facilities and the capacity to accept children. From the perspectives of the safety of and care for sick children, and high-risk households (e.g., single mothers and low-income parents), it is imperative to increase the number of care facilities, the capacity to accept children, and the number of municipalities in which care services are accessible to service users from each municipality.

Concerning the cost of sick child care (standard fee of 2,000 yen per day), subjects reported an increased financial burden due to service utilization by more than one child at any one time, the repeated usage of such care, and fees for nursery school in addition to those for sick child care. In Japan, for households who earn a mean annual income of 6.07 million yen, the standard monthly childcare fee for the first child aged <3>

In the present study, we investigated only one prefecture employing a system for reducing care fees; hence, due to the small sample size, we were not able to clarify differences according to the type of household or presence/absence of the above-mentioned agreement. To design policies based on the needs of care service users, it is necessary to investigate the characteristics of care facility users, and assess the existing care-related measures.

Conclusion

Sick child care was utilized mainly by children from double- income nuclear families or single-mother households, primarily because of infectious diseases. The systems for reducing care fees were used by approximately 60% of the single mothers. Parents were able to work free from anxiety due to child raising support, and the benefits that their children received from sick child care. On the basis of difficulties in utilizing sick child care, parents desired improved care services. The results of this study suggest that, to facilitate sick child care based on the needs of service users, there is a need to increase both the number of care facilities and the capacity to accept children, improve the system for reducing care fees, and increase the number of municipalities in which such care is accessible to service users from each municipality.

Acknowledgement

We are very grateful to all those who participated in this study. This study was funded by Grants-in-Aid for scientific research expenses of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (25463472).

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors have no conflicting interest in this study.

References

-

Child Raising Center, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

(2015) New child raising support system.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Director-General of the Equal Employment, Children and Families Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2015) Provision of sick child care.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Cabinet Office (2013) Sick child care.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Japan Sick Childcare Association (2016) Concept of sick child care.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Yamada Y, Harada K (2009) Roles of sick child care based on a questionnaire survey involving care users. Child Health Ishikawa 21: 7-11.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ishino A, Kato H, Matuda H, Bakke M (2013) Work-life balance and needs in parents used sick childcare service. J Child Health 72: 305-310.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Tanimoto H, Tanimoto K (2016) Need and problems of the sick child care - Considering the results of a questionnaire survey of the parents. J Child Health 65: 593-599.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Tanihara M, Abe H, Mori T, Okada K (2010) Parents’ response to their sick child and the current status of sick-child-care support needs. Kawasaki Med Welf J 19:2, 411-418.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Kamimura A, Kawamoto M, Nagamatsu S, Takahata T, Yokoyama M, et al. (2007) Two-year experience of operating a sick child care facility -Based on past records and the results of a questionnaire survey involving care users-. J Saitama Med Soc 41:4, 309-312.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Nakagawa S, Katsura T (2004) A current situation and problems of the nursery care of sick children – Considering the result of a questionnaire survey of their parents and guardians. J Child Health 63: 389-394.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Kanda T, Miyazu S (2010) Research on childcare nursing at the child care room for sick children: Based on the viewpoint of child care support. Bull Fac Educ, Hirosaki Univ 103: 105-109.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Tanaka Y (2011) The perception of services in nurses as to the day care for sick children. J Child Health 70: 365-370.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Fujiwara Y (2007) The role of an institution for day care for sick children: Focusing on evaluation of the staff. Jpn Soc Res Early Child Care Educ 45: 183-190.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Kanaizumi S, Nakashita T, Yajima M, Ohno A (2003) Characteristics of nursing and nursing intervention skills required in a nursery room for children recovering from common illnesses. Bull Gumma Paz Gakuen College 5: 87-97.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2012) Nationwide survey on fatherless families for 2011.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2011) Overview of comprehensive survey regarding living conditions for 2010.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Sato M (2006) Research into the needs of day nursery users for children with sickness. J Jpn Red Cross Toyota College Nurs 2: 29-34.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Arai K, Yasunari T, Ota C, Sakashita R, Katada N (2012) Responses to illness among the children of working mothers and their needs. J Gen Fam Med 35: 27-36.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Fukada M, Minamimae K, Kasagi T (2001) Analysis of a method of sick child care and nursing role. J Yonago Med Assoc 52: 183-195.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2010) Outline of the child care and family care leave law.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar