Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/BRCA-25-RA-021

Market Fire Victims’ Panic Pain Control: Do Rapid Response, Disaster Aid and Consoled Play a Role in Ghana?

Abstract

Background: For Ghanaian traders, markets are more than economic spaces. They are places of shared experiences, identity, and stability. Therefore, if those places are engulfed in fire, it disrupts these aspects, leading to trauma and shock, grief and loss, anxiety and uncertainty, and depression. Based on this, the study aimed at investigating how rapid response, disaster aid and consoled play a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana.

Methods: Descriptive cross-sectional design was used with 759 participants. Data were analysed with frequency distribution, chi-square and logistic regression. The logistic regression was used to identify the influences the explanatory variables exert on the outcome variable.

Results: The study found that market fire victims’ panic pain control was influenced by secondary education at p<0.001, (OR=2.184, 95%CI ([1.265-3.773]). Generous listening ear at p=0.034, (OR=0.619, 95%CI ([0.397-0.965]). Financial support at p=0.036, (OR=1.606, 95%CI ([1.032-2.499]). Felt belonged at p<0.001, (OR=2.229, 95%CI ([1.386-3.584]).

Conclusion: The study recommends that while preventive measures like improved safety protocols are essential, equal emphasis must be placed on addressing the mental health needs of traders (victims) to support recovery and resilience building.

Introduction

Experiencing a fire outbreak can be one of the most traumatic events in a person’s life [1-3]. It has been established that, an estimated 150,000 people die from fire or burn-related injuries every year, with over 95% of fire deaths and injuries in low-and middle-income countries [4-6]. For years, Ghanaian markets have been plagued by a cycle of fires which leaves behind widespread destruction, impacting not only the physical spaces where livelihoods are built but also the mental and emotional well-being of traders [7-9]. In Ghana, markets are the heartbeat of many communities, providing income, social connections, and a sense of identity for thousands [7]. When these spaces are ravaged by fire, the consequences extend far beyond financial losses, deeply affecting the mental health of those who depend on them. For Ghanaian traders, markets are more than economic spaces. They are places of shared experiences, identity, and stability [7-9]. Therefore, if those places are engulfed in fire, it disrupts these aspects, leading to trauma and shock, grief and loss, anxiety and uncertainty, and depression [7].

Unfortunately, recently, Ghana recorded fire outbreaks at major market centres such as Kantamanto, Kwadaso Wood Market in Kumasi, Timber Market in Tamale, Techiman Central Market, and Kumasi Central Market [7,10]. Beyond the statistics and destruction lie deeply emotional stories of resilience and despair [11,12]. In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, survivors are often left in a state of shock while struggling with anxiety over safety and recovery [13]. Even those who are not directly impacted by a disaster may still experience trauma due to the potential threat of their area being affected, evacuating to avoid the danger, having loved ones in harm’s way, or watching the event unfold on the news [14-16]. While every person reacts to these experiences differently, it is normal for disasters to have some degree of impact on mental health [17-19]. People who experience or witness a disaster, often feel intense emotions that can last long after the initial danger has passed [18-20]. Sometimes even learning second-hand about a loved one’s experience of a trauma can evoke strong feelings. While individual responses following a disaster vary from person to person, four core emotions are almost universal reactions: fear/anxiety, sadness/depression, guilt/shame, and anger/irritability [21,22].

A timely and effective response to fire outbreak is vital [23,24]. The longer it takes for the fire department to respond to a fire incident, the higher the loss incurred in terms of property, health, and lives [25]. Most of the time, the trauma and loss experienced can be mitigated somewhat by the financial support and disaster aid that Philanthropists and state programs provide [26,27]. Moreover, victims can also be consoled emotionally by listening to them, showing empathy, offering comfort, assisting them in cleanup and/or encouraging hope are also helpful [28,29].

In pursuit of identifying previous studies in Ghana on this phenomenon yielded four studies which looked at different aspects of the phenomena. For instance: Oppong et al. [30] examined the fire emergency response in Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly; Addai, Tulashie, Annan and Yeboah [31] studied the trend of fire incidents occurring in Ghana from 2000 to 2013 and the different ways to prevent these incidents; Oteng-Ababio, Sarfo and Owusu-Sekyere [32] explored the socio-economic and institutional factors that underpin the unflinching resilience of survivors of market fire incident while Aning-Agyei, Aning-Agyei, Osei-Tutu and Kendie [33] assessed the economic effect of market fire disasters on victims in Ghana. It will interest you to note that none of the studies above has its aim tilted towards the phenomena under study thus “do rapid response, disaster aid and consoled play a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana?” Based on this, the study attempts to investigate how rapid response, disaster aid and consoled play a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana. Specifically, the study seeks to:

- analyse if rapid response plays a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana;

- ascertain whether disaster aid plays a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana;

- examine if consoled plays a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana; and

- determine if socio-demographic characteristics play a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana.

The study further hypothesised that socio-demographic characteristics, rapid response, disaster aid and consoled do not influence panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

The study took place at Makola, Kantamanto, and Kumasi central markets. These market centres were selected because they were most affected in terms of number and physical scale of destruction [33]. Again, the statistics (12, 933) from those market fire victims satisfy the need for the study. The population of market traders across Makola 10,000 [34]; Kantamanto 8,000 [35] and Kumasi Central 20,000 [36] is 38000. The population affected comprised 12,933 market fire victims across Makola (3,985), Kantamanto (4,527) and Kumasi Central (4,421) Markets in 2012 and 2013 [33].

Study Design and Data Source

The study employed descriptive cross-sectional design. The design was chosen because it looks at data at a single point in time [37]. The design helps in selecting participants based on particular variables [38]. Data were collected from the field from 759 participants with questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed based on literature and previous standardised survey instruments [39-43].

Sample and Sampling Procedure

A sample of 759 were recruited for the study with the help of Cochran’s [44] sample size formula for estimating sample size. With the help of this formula, sample size was estimated at 345 as follows:

n = z2 p (1─p)

d2

n = sample size

Confidence level set at 95% (1.96)

The p-value set at 0.05.

z = standard normal deviation set at 1.96

d = degree of accuracy desired at 0.05

p = proportion of affected population was 34%. Since the population affected comprised 12,933 market fire victims across Makola (3,985), Kantamanto (4,527) and Kumasi Central (4,421) Markets in 2012 and 2013 [33]. Therefore, the proportion was obtained by dividing the affected population by the population of traders (10,000; 8,000; and 20,000) of Makola, Kantamanto and Kumasi Central respectively. Thus, dividing 12,933 by the total population of traders at all the three market centres (38,000) gives 0.34. Mathematically, 12,933/ 38000 = 0.34.

n = 1.962 *0.34 (1─0.34)

0.052

= 344.822, approximately 345.

After the calculation, the sample size was 345. Assuming 10% non-response rate, design effect of 2, (to compensate the design effect) the sample size is: N = 345×2+10% ???????? 690=690+69=759. This brought the estimated sample size to 759. Hence, the larger the sample size, the more insightful information, identification of rare side effects, lesser margin of error, higher confidence level, and models with more accuracy [45].

To reach the participants, the study drew much on multistage sampling technique. Stage 1 was the selection of the three affected market centres (Makola, Kantamanto and Kumasi Central markets). Stage 2 was signing of proportion (253) to each selected market center. This proportion was based on the physical scale of destruction. Stage 3, a systematic sampling approach was adopted to reach the participants. This approach was used because it enabled us select the participants at a regular interval which was determined in advance. So, at Makola market, number 5 was randomly selected. Therefore, the 5th participant was selected as the first person to be a part of the systematic sample. After that, the 10th participant was added into the sample, so on and so forth (15th, 20th, 25th, and participants till 759). However, at each market center, a proportion of 253 participants were selected so in all 253(3) =759 participants were recruited for the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, you should be a trader of the three Market Centres (Makola, Kantamanto and Kumasi Central) and suffered destruction or being a victim of the market fire outbreak. However, those who were not traders in the three Market Centres above, and traders at the three Market Centres who did not suffer any destruction or were not victims of the market fire outbreak were excluded from the study.

Variables and Measurements

The independent variables (IVs) in the study were rapid response, disaster aid and consoled. Key elements of a rapid response include (prompt notification and activation, pre-planned actions and procedures, rapid deployment of resources, focus on early intervention, clear communication and coordination, evacuation and rescue, confining and extinguishing fire, security and access control, and post-incident assessment and learning) [39].

Disaster aid can be divided into 5 domains [40]; 1). basic assistance (e.g., offering safety, medical care, food, medication, shelter), 2) information (e.g., regarding the incident, developments, whereabouts of loved ones, possible consequences of the incident on health), 3) emotional and social support (e.g., offering a listening ear, recognition), 4), practical assistance (e.g., legal advice, financial support), and 5) (health) care for those individuals with health problems (e.g., prevention, diagnosis, treatment) [41]. While consoled key elements are (ways consoled, console perception, empathy, encouragement, and comfort) [42]. The dependent variable (DV) in the study was panic pain control which has (control over the panic pain, pain reduction, coping actions, and resumption of duty) [43] as indicators.

Data collection Procedure

Data collection took place on February 10, 2025 and ended on February 28, 2025 with the help of five research assistant. Each market centre was contacted separately. In all, nineteen (19) days were used to collect the data. In the field, research assistants were assisted with the tablet computers to collect the data.

Data Processing and Analysis

Data were analysed with SPSS on questionnaire response rate of 559/759×100=74% with alpha coefficient of 0.7. Generally, Adadan and Savasci [46] postulated that alpha coefficient of 0.70 offers evidence of acceptability, indicating that the instrument has good internal consistency and that data is acceptable for analysis. Three different analysis were conducted on the data using frequency distribution, chi-square test and binary logistic regression. The frequency distribution was used to summarise respondents’ responses into proportion. The Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence was used to test the hypotheses postulated in the study to either accept or reject the null hypotheses. The binary logistic regression was used to determine the influences of the rapid response, disaster aid and consoled on market fire victims panic pain control.

Ethical Consideration

The study did not seek any ethical approval. However, in the field, participants were briefed about the purpose of the study and why it will be beneficial if they let us know how those variables studied in the study interplay to help them control their panic pain for policy recommendation. Based on this, participants voluntarily owned out to assist us reach our prime goal for the study. Hence, an oral consent was sought. Privacy, confidentiality and anonymity were all adhered to in the field.

Results

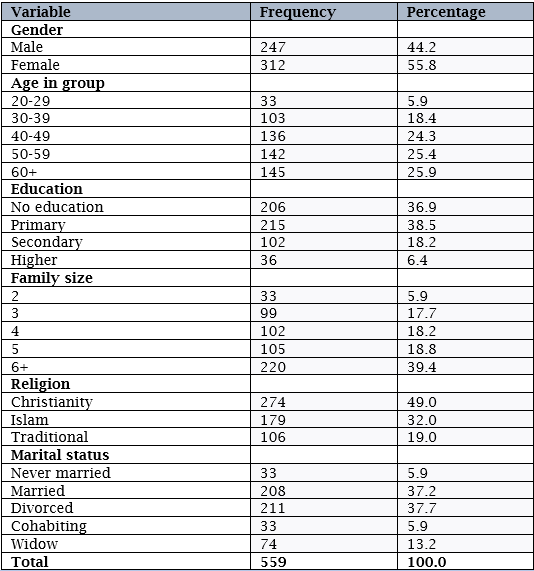

The study comprised 56?males and 44% males. Whereas 26?long to 60years and above age group category, about 6% were in the 20-29 age group. About 37% had no education while 6% had higher education. Whereas 39% had 6 and above members in the family about 6% had 2 members in the family. On religion, 49% were Christians while 19% sympathise with the traditional belief. Whereas 38% were divorced 6% were never married (see Table 1).

Source: Fieldwork (2025).

To be able to identify among the market fire victims those who were able to control their panic pain during the fire outbreak made us asked questions spanning from (panic pain control, and ways of pain reduction). When asked whether participants were able to control the panic pain encountered during the market fire outbreak or not, the results revealed that 81% intimated they were able to control the pain while 19% said they were not able to control the pain. The 453 (81%) participants that reported they were able to control the panic pain were further asked to indicate the ways they controlled the pain. The results revealed that 39% of the participants reported resumption of normal activities 38% indicated they consoled themselves while 23% said they adopted coping actions.

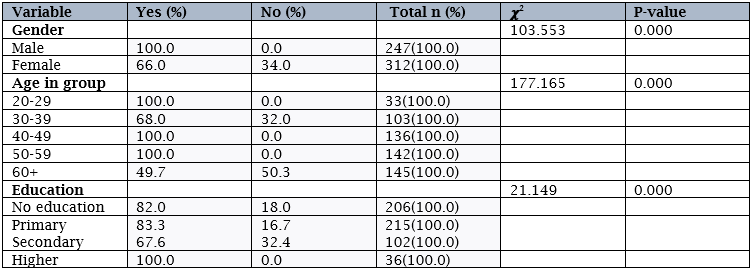

The study attempted to ascertain whether there exists a relationship between participants’ socio-demographic characteristics and panic pain control. This analysis was conducted with Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence to test the hypothesis there is no statistically significant relationship between participants’ socio-demographic characteristics and panic pain control. Statistically significant relationships were found between all the variables studied under socio-demographic characteristics of participants. Namely: Gender [????2=103.553, p<0>2=177.165, p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>

Note: Row percentages in parenthesis, Chi-square significant at (0.001), (0.05), (0.10)

Yes: controlled; No: unable to control.

Source: Fieldwork (2025).

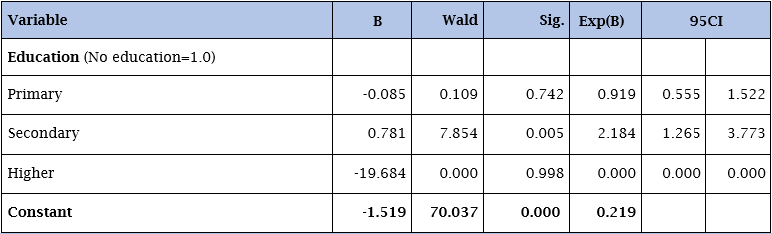

Table 3 has outcome of binary logistic regression of socio-demographic characteristics of panic pain control among market fire victims. This analysis was conducted on six (6) items which includes (sex, age, education, family size, religion, and marital status) to determine those that influence panic pain control among market fire victims. The results are presented in Table 3.

Source: Fieldwork (2025). Significant at 0.05.

After processing the data, only education was significant. Those that were not significant were removed from the model (see Table 3). Overall, the logistic regression model was significant at -2LogL = 516.666; Nagelkerke R2 of 0.074; ????2= 26.321; p<0>

Table 3 revealed that secondary education was statistically significant related to market fire victims’ panic pain control at p<0 OR=2.184,>

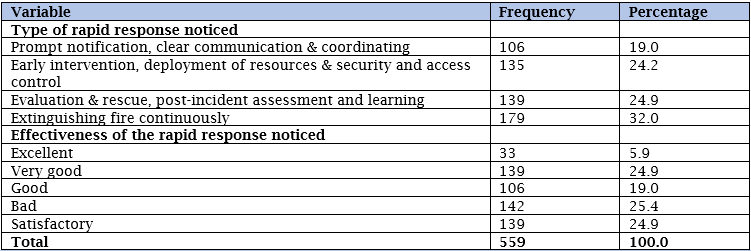

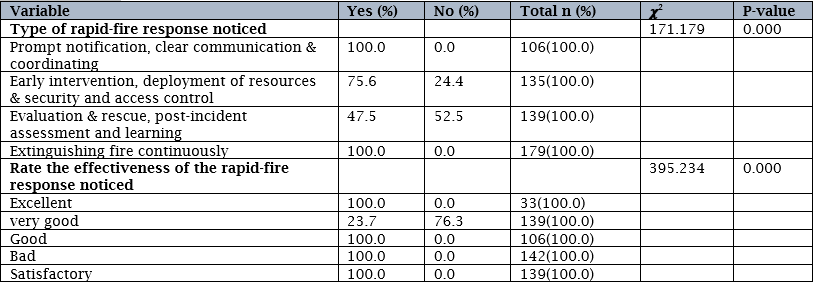

In pursuit of satisfying our curiosity on how rapid response play a role in panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana requested us to ask questions spanning from (prompt notification and activation, pre-planned actions and procedures, rapid deployment of resources, focus on early intervention, clear communication and coordination, evacuation and rescue, confining and extinguishing fire, security and access control, and post-incident assessment and learning). The results are presented in Table 4.

Source: Fieldwork (2025).

When asked about the type of rapid response noticed during the market fire outbreak revealed that 32% indicated extinguishing fire continuously while 19% said prompt notification, clear communication and coordinating (see Table 4). Whereas 25% of the participants rated the rapid response noticed as bad 6% rated it as excellent (see Table 4).

Further analysis was conducted with Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence. This analysis was necessary to test the hypothesis there is no statistically significant relationship between rapid response and panic pain control among market fire victims. Statistically significant relationship was found in all the variables namely: type of rapid response noticed [????2=171.179, p<0>p<0>

Note: Row percentages in parenthesis, Chi-square significant at (0.001), (0.05), (0.10)

Yes: controlled; No: unable to control.

Source: Fieldwork (2025).

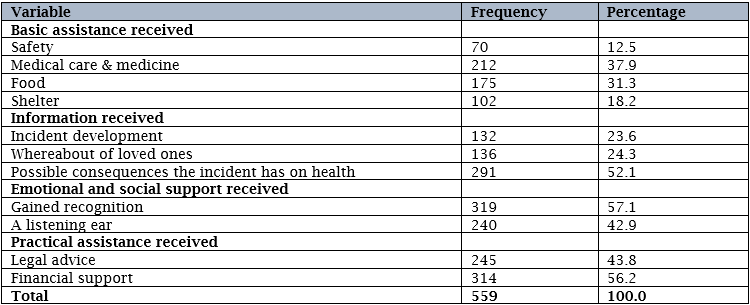

Table 6 has outcome of disaster aid market fire victims received. Participants were asked questions spanning from (basic assistance, information, emotional and social support, practical assistance, and ([health] care for those individuals with health problems) just to identify the kind of disaster aid they received.

When participants were asked about the basic assistance received during the market fire outbreak, the results revealed that about 38% reported medical care and medicine while 13% indicated safety (see Table 6). Whereas 52% reported that information received was possible consequences the incident has on health about 24% indicated incident development (see Table 6). Concerning emotional and social support received, 57% indicated they gained recognition while 43% said people listened to their plea (see Table 6). Whereas 56% intimated financial support was the practical assistance received 44% indicated legal advice (see Table 6).

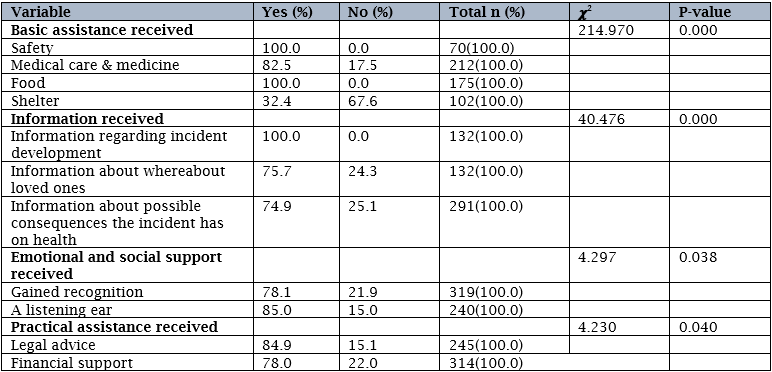

Further analysis was conducted with Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence. This analysis was conducted to test the hypothesis there is no statistically significant relationship between disaster aid and panic pain control among market fire victims. Statistically significant relationship was found among all the variables studied under disaster aid namely: Basic assistance received [????2=214.970, p<0>p<0>p=0.038] as well as practical assistance received [????2=4.230, p=0.040] and panic pain control among market victims (see Table 7).

Note: Row percentages in parenthesis, Chi-square significant at (0.001), (0.05), (0.10)

Yes: controlled; No: unable to control.

Source: Fieldwork (2025).

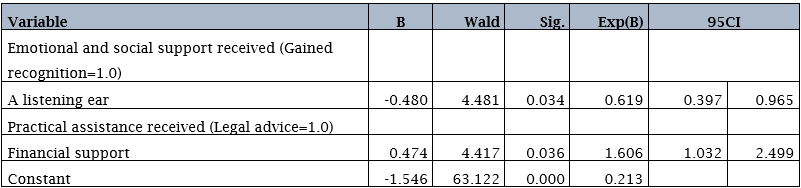

Table 8 has outcome of binary logistic regression of disaster aid and panic pain control among market fire victims. This analysis was conducted on six (6) items which includes (basic assistance received, information received, emotional and social support received, practical assistance, ways consoled, how perceived the console) to ascertain those that predict panic pain control among market fire victims.

Source: Fieldwork (2025). Significant at 0.05.

After processing the data, only two variables (emotional and social support received, and practical assistance received) were significant. Those that were not significant were removed from the model (see Table 8). Overall, the logistic regression model was significant at -2LogL = 534.074; Nagelkerke R2 of 0.025; ????2= 8.914; p=0.012 with correct prediction rate of 81.0%. More importantly, the Model Summary which shows a Nagelkerke R2 of 0.025 suggests that the model explains 2.5% of variance in the likelihood of panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana. With this percentage contribution to the entire model, the results confirmed the whole model significantly predict panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana.

Table 8 revealed that generous listening ear was statistically significant related to panic pain control among market fire victims at p=0.034, (OR=0.619, 95%CI ([0.397-0.965]). This factor classifies those market fire victims to have 0.62times less likely to control panic pain compared with their counterparts that reported they gained recognition (see Table 8). Further, financial support was statistically significant related to panic pain control among market fire victims at p=0.036, (OR=1.606, 95%CI ([1.032-2.499]). This factor categorises those market fire victims to have 1.61times more likely to control panic pain compared with their counterparts that reported they gained recognition (see Table 8).

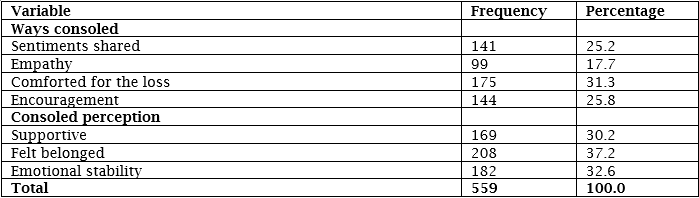

To unravel the consoled market fire victims received during the outbreak instigated questions which includes (ways consoled, consoled perception, encouragement, and comfort). The results are presented in Table 9.

Source: Fieldwork (2025).

When participants were asked to determine ways, they were consoled during the market fire outbreak, 31% reported they were comforted for the loss while 18% indicated empathy (see Table 9). On consoled perception, 37% indicated they felt belonged while 30% said it was supportive (see Table 9).

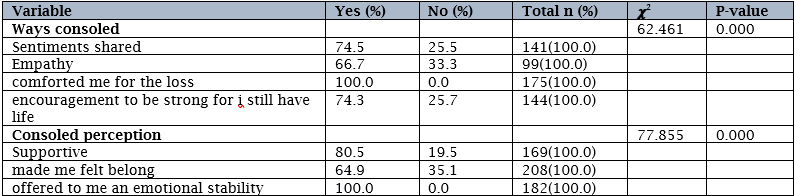

Further analysis was conducted with Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence to determine whether a relationship exists between consoled and panic pain control among market fire victims. This analysis was essential to test the hypothesis there is no statistically significant relationship between consoled and panic pain control among market fire victims. Statistically significant relationships were found in all the variables studied under consoled. Namely: Ways consoled [????2=62.461, p<0>p<0>

Note: Row percentages in parenthesis, Chi-square significant at (0.001), (0.05), (0.10)

Yes: controlled; No: unable to control.

Source: Fieldwork (2025).

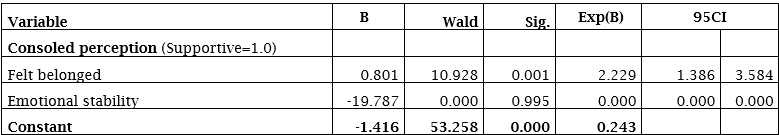

Table 11 has outcome of binary logistic regression of consoled and panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana. This analysis was conducted to determine the influences of the indicators studied under consoled on panic pain control among market fire victims.

Source: Fieldwork (2025). Significant at 0.05.

After processing the data, only consoled perception was significant. The variable that was not significant was removed from the model (see Table 11). Overall, the logistic regression model was significant at -2LogL=436.479; Nagelkerke R2 of 0.279; ????2= 106.509; p<0>

Table 11 revealed that felt belonged was statistically significant related to panic pain control among market fire victims at p<0 OR=2.229,>

Discussion

Opinions on a vast number of topics differ between individuals associated with different categories of sociodemographic characteristics. For example, in the study, it was found that market fire victims that had secondary level of education had higher odds of panic pain control compared with their counterparts who had no education. The plausible explanation could be that education has made these individuals to understand what pain is and had different thought about pain which invariably helped them to bring the pain under control. Further, it could be that these individuals never engaged in thoughts, emotions, and activity that could have escalated the sensitivity of the nervous system which could have made them felt the pain often and intensely. This finding confirms a study which found that persons with higher levels of education may have more practice or more success in using strategies that involve complex cognitions about pain compared with participants with lower education or no education [47].

Statistically significant relationship was found between socio-demographic characteristics and panic pain control among market fire victims. Therefore, the null hypothesis was not approved. A p-value of <0>

The study found that participants had varied views regarding rapid response to market fire outbreak. Based on the varied views they had, they graciously cited extinguishing fire continuously, evaluation and rescue, post-incident assessment and learning, early intervention, deployment of resources and security and access control, and prompt notification, clear communication and coordinating as the rapid response noticed during the fire outbreak. The ability to respond rapidly to market fire is crucial in mitigating the impact and ensuring the safety and well-being of victims. Rapid response serves as a critical component of incident management. By swiftly addressing an incident, organisations can minimise downtime, prevent further damage, and ultimately save lives. The ability to assess the situation promptly, mobilise resources efficiently, and provide immediate assistance can make all the difference in saving lives and minimising harm. This finding is consistent with previous studies which found that during the fire, the following are needed: a timely response; well organized evacuation of patients; espirite de corps among all the healthcare workers; a round-the-clock functional command centre; and effective communication [50, 51].

The study found that 75% of the participants appreciated the rapid response noticed during the market fire outbreak. The possible explanation to this finding could partly be that the rapid response they witnessed was able to bring the situation under control. This finding is consistent with previous studies which found that emergency response to accidents have yielded considerable functions, successfully serving as efficient rescue and risk reduction. Also, a larger emergency response framework, coordination with other emergency processes in the country increases the likelihood of a successful response [52,53]. However, the one-fourth (25%) participants that rated the effectiveness of the rapid response noticed as bad, reason could be that the rapid response could not mitigate or minimise the impact of the fire which made it to escalate into larger-scale crises thereby increasing damages and losses. This finding corroborated with a study which found that public health emergency response in sub-Saharan Africa is constrained by inadequate skilled public health workforce and underfunding [54].

The study found that a statistically significant relationship exists between rapid response and panic pain control among market fire victims in Ghana. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected. A p-value of <0>

The study found that the basic assistance victims received after the market fire were medical care and medicine, food, shelter, and safety. This finding suggests that the government, stakeholders and other non-governmental organisations are aware that disaster can change victims’ attitudes in ways that can potentially haunt their prosperity for decades to come. Therefore, after the emergency phase of a response has been completed, delivering disaster aid to victims quickly not only restores lost assets, but also maintains their aspirations—and invests in communities’ longer-term economic and democratic health. Disaster aid provides vital short-term and long-term support to people affected by disasters, helping them with immediate needs like food and shelter, and assisting with recovery and rebuilding their lives. When disaster victims are allowed to endure disasters without aid, they may face a lifetime of diminished hope for prosperity. This finding is in line with a previous study which found that the focus of rapid needs assessments mainly on (physical and mental) health care needs and basic needs (including acute medical care) is understandable, as these needs are generally the most pressing (especially in the acute phase), and can be assessed relatively quickly [57].

Statistically significant relationship was identified between disaster aid and panic pain control among market fire victims. Therefore, the null hypothesis was refuted. This finding suggests that the more and more market fire victims receive disaster aid it is the more and more it increases their odds of panic pain control. The p-value (<0 p = 0.008) p = 0.016)>

Generally, generous listening offers scalable practises that enable people to navigate crises or traumatic events such as fire outbreak with ease. However, the study found participants who reported a listening ear as the emotional and social support received to have lower odds of a panic pain control compared with their counterparts that indicated they gained recognition. The plausible explanation to this finding could be that this generous listening was unable to instill hope, build trust, promote shared values and foster harmonious living among victims. Further, it could be that this generous listening could not create a space to allow victims to express themselves freely without any intervention which eventually left them in dismayed and made them to feel isolated. This result disagrees with a study which found that music listening was associated with higher levels of perceived control over pain [60].

The study found participants that indicated financial support as the practical assistance received after experiencing a disaster to have higher odds of panic pain control compared with their counterparts that reported legal advised. This finding suggests that financial support after disaster, provides funds for recovery. Disasters happen unexpectedly and the devastating damage and consequences victims encounter are difficult to predict. Therefore, the financial support enables them rebuild their homes and return to their normal way of life. This finding is in line with previous studies which found that a strong relationship exists between financial worries, employment for wages, income, and self-reported chronic pain. The authors further posited that, having no employment with wages was strongly associated with increased risk for chronic pain [61,62].

The study found that market fire victims were consoled in different ways stemming from comforted for the loss, encouragement, sharing of sentiments, and empathy of which they had varied perceptions about the consoled received. This outcome is in line with previous studies which found that victims can be consoled emotionally by listening to them, showing empathy, offering comfort, assisting them in cleanup and/or encouraging hope are also helpful [28,29]. With the consoled perception, more than thirty per cent (37%) indicated felt belonged, 33?lt emotionally stable, and 30?lt it was supportive. The findings indicate that, when disasters strike, survivors normally experience a range of psychological reactions. The total loss of places, memories, and even loved ones, can feel overwhelming and cause serious emotional damage. People affected by these events may experience a wide range of emotions, from fear and sadness to shock and confusion. And the effects can be long-lasting and may even result in mental health challenges and even post-traumatic stress disorder. While words alone cannot fix everything, they can bring comfort and strength to victims facing a difficult situation. Sometimes, knowing that someone cares about you is the most powerful support of all. This finding agrees with a study which found that the consoled fire victims received minimises confusion in their lives and keeps their minds in peace [63].

The relationship found between consoled and panic pain control among market fire victims indicates that market fire victims had an increased odds of panic pain control. This finding suggests that, if a disaster victim is consoled, it goes a long way to enable the victim to bring the pain under control and move on with life. Based, on this relationship, the null hypothesis was not confirmed.

The study found participants that reported felt belonged as the consoled perception to have higher likelihood of panic pain control compared with their counterparts that indicated supportive. In disaster situations, a strong sense of belonging and social support can suggestively improve panic pain control and recovery by mitigating stress and promoting coping mechanisms. The finding is similar to a study which found that fear of pain is known to influence pain perception and worsen pain outcomes [64].

Limitations of the Study

Though effort was made to minimise errors in the study. However, the use of cross-sectional design made it impossible. We were incapacitated to establish cause-and-effect relationships. Again, since data was collected at a single point in time, it made it unsuitable for analysing behaviour across a period. Further, the study is a sample not census. Therefore, generalisability was not possible and that the results should be interpreted with caution

Conclusion

Market fires are tragic events that leave behind widespread destruction, impacting not only the physical spaces where livelihoods are built but also the mental and emotional well-being of traders. Based on this, the study recommends that while preventive measures like improved safety protocols are essential, equal emphasis must be placed on addressing the mental health needs of traders (victims) to support recovery and resilience building. Also, a container of fire-fighting equipment in the open spaces within the market centres be made available.

Acknowledgements

Sincerely, we are grateful to the participants who sacrifice their time to take part in the study and the research assistants for their help during the data collection.

Declaration

Ethical Approval

The study did not seek any ethical approval. However, in the field, participants were briefed about the purpose of the study and why it will be beneficial if they let us know how those variables studied in the study interplay to help them control their panic pain for policy recommendation. Based on this, participants voluntarily owned out to assist us reach our prime goal for the study. Hence, an oral consent was sought. Privacy, confidentiality and anonymity were all adhered to in the field.

References

-

Lodha P, Shah B, Karia S, De Sousa A. (2020). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Ptsd) Following Burn Injuries: A Comprehensive Clinical Review. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 33(4):276-287. PMID: 33708016; PMCID: PMC7894845.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Oliveira J, Aires Dias J, Duarte IC, Caldeira S, Marques AR, Rodrigues V, Redondo J & Castelo-Branco M (2023). Mental health and post-traumatic stress disorder in firefighters: an integrated analysis from an action research study. Front. Psychol. 14:1259388. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1259388.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Shokouhi M, Nasiriani K, Cheraghi Z, Ardalan A, Khankeh H, Fallahzadeh H, & Khorasani-Zavareh D. (2018). Preventive measures for fire-related injuries and their risk factors in residential buildings: a systematic review. J Inj Violence Res. 2019 Jan;11(1):1-14. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v11i1.1057. Epub. PMID: 30416192; PMCID: PMC6420922.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Forbinake NA, Ohandza CS, Fai KN, Agbor VN, Asonglefac BK, Aroke D, Beyiha G. (2020). Mortality analysis of burns in a developing country: a CAMEROONIAN experience. BMC Public Health. 20(1):1269. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09372-3. PMID: 32819340; PMCID: PMC7441696.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Rush, D. et al. (2019). Fire risk reduction on the margins of an urbanizing world. Contributing Paper to GAR 2019. Retrieved on 02/04/2025 from: https://www.undrr.org/publication/fire-risk-reduction-margins-urbanizing-world#:~:text=It%20is%20estimated%20more%20than,-%20and%20middle-income%20countries.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Rybarczyk MM, Schafer JM, Elm CM, Sarvepalli S, Vaswani PA, Balhara KS, Carlson LC, Jacquet GA. (2017). A systematic review of burn injuries in low- and middle-income countries: Epidemiology in the WHO-defined African Region. Afr J Emerg Med. 7(1):30-37. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.01.006. Epub 2017 Jan 28. PMID: 30456103; PMCID: PMC6234151.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Citi News Room (March 24, 2025). Ghana’s market inferno: A tale of destruction and despair – Towfik Mohammed writes. Retrieved on 02/04/2025 from: https://citinewsroom.com/2025/03/ghanas-market-inferno-a-tale-of-destruction-and-despair-towfik-mohammed-writes/

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Modern Ghana (25 March, 2025). Market Fires in Ghana: A Call for Sustainable and Modern Solutions. Retrieved on 02/04/2025 from: https://www.modernghana.com/news/1388649/market-fires-in-ghana-a-call-for-sustainable.html.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

ZED Multimedia New Vision (January 16, 2025). Market fire victims need psychological counselling. Retrieved on 02/04/2025 from: https://zedmultimedia.com/2025/01/16/market-fire-victims-need-psychological-counselling/

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ghana Web (3 February 2025). 5 times markets in Ghana were ravaged by fire in January 2025. Retrieved on 02/04/2025 from: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/5-times-markets-in-Ghana-were-ravaged-by-fire-in-January-2025-1969967. Article 1969967.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Wiseman, J. (2021). Hope and Courage in a Harsh Climate: From Denial and Despair to Resilience and Transformation. In: Brears, R.C. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Climate Resilient Societies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42462-6_130.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Varutti, M. (2024). Claiming ecological grief: Why are we not mourning (more and more publicly) for ecological destruction? Ambio 53, 552–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-023-01962-w.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Makwana N. (2019). Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(10):30903095. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6857396/. Accessed Oct 14, 2022. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Lee JY, Kim SW, & Kim JM. (2020). The Impact of Community Disaster Trauma: A Focus on Emerging Research of PTSD and Other Mental Health Outcomes. Chonnam Med J. 2020 May;56(2):99-107. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2020.56.2.99. Epub 2020 May 25. PMID: 32509556; PMCID: PMC7250671.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Heanoy, E. Z., & Brown, N. R. (2024). Impact of Natural Disasters on Mental Health: Evidence and Implications. Healthcare, 12(18), 1812. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12181812.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Morganstein JC & Ursano RJ (2020) Ecological Disasters and Mental Health: Causes, Consequences, and Interventions. Front. Psychiatry 11:1. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00001.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Felix ED, & Afifi W. (2015). The Role Of Social Support On Mental Health After Multiple Wildfire Disasters: Social Support and Mental Health After Wildfires. Journal of community psychology. 2015;43(2):156-170. doi:10.1002/jcop.21671.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Heanoy EZ, Brown NR. (2024). Impact of Natural Disasters on Mental Health: Evidence and Implications. Healthcare (Basel). 12(18):1812. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12181812. PMID: 39337153; PMCID: PMC11430943.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Makwana N. (2019). Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019 Oct 31;8(10):3090-3095. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19. PMID: 31742125; PMCID: PMC6857396.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Jiménez-Herrera, M.F., Llauradó-Serra, M., Acebedo-Urdiales, S. et al. (2020). Emotions and feelings in critical and emergency caring situations: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs 19, 60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-020-00438-6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Massazza A, Brewin CR, & Joffe H. (2020). Feelings, Thoughts, and Behaviors During Disaster. Qual Health Res. 2021 Jan;31(2):323-337. doi: 10.1177/1049732320968791. Epub 2020 Nov 23. PMID: 33228498; PMCID: PMC7753093.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Amiri, H., & Jahanitabesh, A. (2023). Psychological Reactions after Disasters. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.109007.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Banach DB, Johnston BL, Al-Zubeidi D, Bartlett AH, Bleasdale SC, Deloney VM, Enfield KB, Guzman-Cottrill JA, Lowe C, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Popovich KJ, Patel PK, Ravin K, Rowe T, Shenoy ES, Stienecker R, Tosh PK, & Trivedi KK. (2017). Outbreak Response Training Program (ORTP) Advisory Panel. Outbreak Response and Incident Management: SHEA Guidance and Resources for Healthcare Epidemiologists in United States Acute-Care Hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 38(12):1393-1419. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.212. Epub 2017 Nov 30. PMID: 29187263; PMCID: PMC7113030.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Sahebi A, Jahangiri K, Alibabaei A, & Khorasani-Zavareh D. (2021). Factors Influencing Hospital Emergency Evacuation during Fire: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Prev Med. 12:147. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_653_20. PMID: 34912523; PMCID: PMC8631117.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Shokouhi M, Nasiriani K, Cheraghi Z, Ardalan A, Khankeh H, Fallahzadeh H, Khorasani-Zavareh D. Preventive measures for fire-related injuries and their risk factors in residential buildings: a systematic review. J Inj Violence Res. 2019 Jan;11(1):1-14. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v11i1.1057. Epub 2018 Nov 11. PMID: 30416192; PMCID: PMC6420922.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ratcliffe, C., Congdon, W., Teles, D., Stanczyk, A., & Martín, C. (2020). From Bad to Worse: Natural Disasters and Financial Health. Journal of Housing Research, 29(sup1), S25–S53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10527001.2020.1838172.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Varshney K, Makleff S, Krishna RN, Romero L, Willems J, Wickes R, & Fisher J. (2023). Mental health of vulnerable groups experiencing a drought or bushfire: A systematic review. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 10:e24. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2023.13. PMID: 37860103; PMCID: PMC10581865.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Babaii A, Mohammadi E, & Sadooghiasl A. (2021). The Meaning of the Empathetic Nurse-Patient Communication: A Qualitative Study. J Patient Exp. 8:23743735211056432. doi: 10.1177/23743735211056432. PMID: 34869836; PMCID: PMC8640307.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis A, & Koukouli S. (2020). The Role of Empathy in Health and Social Care Professionals. Healthcare (Basel). 8(1):26. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8010026. PMID: 32019104; PMCID: PMC7151200.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Oppong, et al. (2016). Emergency fire response in Ghana: the case of fire stations in Kumasi. African Geographical Review. 36. 1-9. 10.1080/19376812.2016.1231616.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Addai EK, Tulashie SK, Annan JS, & Yeboah I. (2016). Trend of Fire Outbreaks in Ghana and Ways to Prevent These Incidents. Saf Health Work. 7(4):284-292. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2016.02.004. Epub 2016 Mar 9. PMID: 27924230; PMCID: PMC5127973.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Oteng-Ababio, M., Sarfo, K.O., & Owusu-Sekyere, E. (2015). Exploring the realities of resilience: Case study of Kantamanto Market fire in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 12, 311-318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.02.005.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Aning-Agyei, P.G., Aning-Agyei, M.A., Osei-Tutu, B., & Kendie, S.B. (2025). Assessing the economic effects of market fire disasters on businesses in Ghana. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 118, 105274 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2025.105274.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

The Ghana Circular (July 21, 2023). The Makola Market, Accra. Retrieved on 25/3/2025 from: https://theghanacircular.com/the-makola-market-accra/

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

CDS Africa (January 11, 2025, 11: 23pm) Kantamanto Market Fire: Putting a Human Face to the Tragedy and the Need for Government Intervention. Retrieved on 25/3/2025 from: https://www.cdsafrica.org/kantamanto-market-fire-putting-a-human-face-to-the-tragedy-and-the-need-for-government-intervention/#:~:text=As%20the%20world%27s%20largest%20secondhand,it%20for%20their%20daily%20sustenance.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Okoye, V. (2020). “Street Vendor Exclusion in “Modern” Market Planning: A Case Study from Kumasi, Ghana

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Capili B. (2021). Cross-Sectional Studies. Am J Nurs. 121(10):59-62. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000794280.73744.fe. PMID: 34554991; PMCID: PMC9536510.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. (2019). Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies. Perspect Clin Res. 10(1):34-36. doi: 10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18. PMID: 30834206; PMCID: PMC6371702.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Saeed, M., Swaroop, M., Yanagawa, F. S., Buono, A., & Stawicki, S. P. (2018). Avoiding Fire in the Operating Suite: An Intersection of Prevention and Common Sense. InTech. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.76210.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Jacobs, J., Oosterbeek, M., Tummers, L.G., Noordegraaf, M., Yzermans, C.J., Dückers, M.L.A. (2019). The organization of post-disaster psychosocial support in The Netherlands: a meta-synthesis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol., 10 (1), 1544024.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Dückers, M.L.A., & Thormar, S.B. (2015). Post-disaster psychosocial support and quality improvement: a conceptual framework for understanding and improving the quality of psychosocial support programs, Nurs. Health Sci., 17 (2), 159-165.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Babaii A, Mohammadi E, Sadooghiasl A. (2021). The Meaning of the Empathetic Nurse-Patient Communication: A Qualitative Study. J Patient Exp. 8:23743735211056432. doi: 10.1177/23743735211056432. PMID: 34869836; PMCID: PMC8640307.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Tunnell NC, Corner SE, Roque AD, Kroll JL, Ritz T & Meuret AE (2024) Biobehavioral approach to distinguishing panic symptoms from medical illness. Front. Psychiatry 15:1296569. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1296569.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Cochran, W.G. (1977). Sampling Techniques. 3rd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Gumpili SP, & Das AV. (2022). Sample size and its evolution in research. IHOPE J Ophthalmol, 1, 9-13.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Adadan, E., & Savasci, F. (2011). An analysis of 16-17-year-old students’ understanding of solution chemistry concepts using a two-tier diagnostic instrument. International Journal of Science Education, 34(4), 513–544. doi:10.1080/09500693.2011.636084.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Cano A, Mayo A, & Ventimiglia M. (2006). Coping, pain severity, interference, and disability: the potential mediating and moderating roles of race and education. J Pain. 2006 Jul;7(7):459-68. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.445. Erratum in: J Pain. 2006 Nov;7(11):869-70. PMID: 16814685; PMCID: PMC1894938.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Jonsson A, & Jaldell H. (2020). Identifying sociodemographic risk factors associated with residential fire fatalities: a matched case control study. Inj Prev. 26(2):147-152. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2018-043062. Epub 2019 Mar 4. PMID: 30833287.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Zemni I, Gara A, Nasraoui H, Kacem M, Maatouk A, Trimeche O, Abroug H, Fredj MB, Bennasrallah C, Dhouib W, Bouanene I, & Belguith AS. (2023). The effectiveness of a health education intervention to reduce anxiety in quarantined COVID-19 patients: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 23(1):1188. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16104-w. PMID: 37340300; PMCID: PMC10280925.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Dhaliwal N, Bhogal RS, Kumar A, & Gupta AK. (2018). Responding to fire in an intensive care unit: Management and lessons learned. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(2):154-156. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2018.02.014. PMID: 29576832; PMCID: PMC5847505.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Tijani, E.E., (2021). Managing Rapid Responses to Forest Fires: A Life Saving Hack for Locals and the Environment. Retrieved on 02/04/2025 from: SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3955974 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3955974.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Zhang, S., Liu, X., & Wang. J. (2024). Research on the construction of a “full-chain” rapid response system for power emergencies. Heliyon,10, 4, e26501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26501.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Greiner AL, Stehling-Ariza T, Bugli D, Hoffman A, Giese C, Moorhouse L, Neatherlin JC, & Shahpar C. (2020). Challenges in Public Health Rapid Response Team Management. Health Secur. 18(S1), S8-S13. doi: 10.1089/hs.2019.0060. PMID: 32004121; PMCID: PMC8900190.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Masiira, B., Antara, S.N., Kazoora, H.B., Namusisi, O., Gombe, N.T., Magazani, A.N., Nguku, P.M., Kazambu, D., Gitta, S.N., Kihembo, C., Sawadogo, B., Bogale, T.A., Ohuabunwo, C., Nsubuga, P., & Tshimanga, M. (2020). Building a new platform to support public health emergency response in Africa: the AFENET Corps of Disease Detectives, 2018–2019: BMJ Global Health, 5, e002874.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Kefyalew, M., Deyassa, N., Gidey, U., Temesgen, M., & Mehari, M. (2024). Improving the time to pain relief in the emergency department through triage nurse-initiated analgesia - a quasi-experimental study from Ethiopia. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14 (3), 161-166 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2024.06.004.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Bosmans, M.W.G., Baliatsas, C., Yzermans, C.J., & Dückers, M.L.N. (2022). A systematic review of rapid needs assessments and their usefulness for disaster decision making: Methods, strengths and weaknesses and value for disaster relief policy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 71, 102807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102807.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Tsai CH, Christian M, & Lai F. (2023). Enhancing panic disorder treatment with mobile-aided case management: an exploratory study based on a 3-year cohort analysis. Front Psychiatry. 14:1203194. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1203194. PMID: 37928915; PMCID: PMC10620526.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Jackson T, Pena M, McQueen K, Kucik C. (2020). Pain in Disasters. In: McIsaac J, ed. Essentials of Disaster Anesthesia. Cambridge University Press; 143-156.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Linnemann A, Kappert MB, Fischer S, Doerr JM, Strahler J, & Nater UM. (2015). The effects of music listening on pain and stress in the daily life of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Front Hum Neurosci. 9:434. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00434. PMID: 26283951; PMCID: PMC4519690.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Weissman JD, Russell D, & Taylor J. (2023). The Relationship Between Financial Stressors, Chronic Pain, and High-Impact Chronic Pain: Findings From the 2019 National Health Interview Survey. Public Health Rep. 2023 May-Jun;138(3):438-446. doi: 10.1177/00333549221091786. Epub 2022 May 4. PMID: 35506496; PMCID: PMC10240893.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Sujan MSH, Tasnim R, Islam MS, Ferdous MZ, Haghighathoseini A, Koly KN, & Pardhan S. (2022). Financial hardship and mental health conditions in people with underlying health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Heliyon. 8(9):e10499. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10499. Epub 2022 Aug 31. PMID: 36060462; PMCID: PMC9428118.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Archer, D., & Boonyabancha, S. (2011). Seeing a disaster as an opportunity – harnessing the energy of disaster survivors for change. Environment & Urbanization, 23(2), 351-364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247811410011 (Original work published 2011).

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Motoyoshi, T. (2019). Supporting Disaster Victims. In: Abe, S., Ozawa, M., Kawata, Y. (eds) Science of Societal Safety. Trust, vol 2. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2775-9_17.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Romualdo JM, Borges E, Tavares I, & Pozza DH. (2024). The interplay of fear of pain, emotional states, and pain perception in medical and nursing students: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 19(11):e0314094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0314094. PMID: 39570991; PMCID: PMC11581238.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar