Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/ISSRR-RA-25-003

Expectations in Required Physical Activity Classes: What Do They Really Want?

Abstract

Many universities require up to four one-credit physical activity classes for all undergraduate students to graduate. Each student brings a different level of skill and knowledge, and, perhaps, very different expectations to the class. The purpose of this basic qualitative study was to examine the expectations of students engaged in required physical activity classes, not only to determine what they are, but also to see if they were met. Following Institutional Review Board approval, eight student participants were recruited from activity classes currently taught by the investigator and were interviewed. The findings confirmed several points concerning students’ expectations of required activity classes. All of the students were in favor of college students being involved in physical activity. Almost none of the same students were otherwise involved in a regular, independent physical activity program. Almost none of the students were even aware that physical activity courses were required for graduation. All of the students supported physical activity courses being required. Students’ expectations of what they wanted from physical activity classes were very basic. All of the students were satisfied that their individual expectations had been met. Most students had thought enough about the classes to offer some meaningful suggestions to improve them.

I. Introduction

Lack of physical activity has been cited as a significant health issue among college students by Pauline [1]. College students are often subjected to stress, inadequate sleep, lack of physical activity, and poor eating habits. Recent recommendations to promote and maintain health called for all healthy adults from 18-65 years of age to be engaged in moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity for a minimum of 30 minutes for five days each week or vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity for a minimum of 20 minutes for three days each week. In addition, the recommendations stated that every healthy adult should perform activities to increase and maintain muscle strength and tone for a minimum of two days each week [2]. Required college physical activity classes may help to achieve these goals and to change behavior patterns among students.

Physical education classes have been offered by colleges and universities for over 100 years and many institutions still require up to four one-credit physical activity classes for all undergraduate students to graduate, regardless of their major field of study. Hensley [3] found that among the 386 institutions responding to his questionnaire, 47 percent had a two-credit requirement, 21 percent had a three-credit requirement, 14 percent had a four-credit requirement, and 18 percent required more than four-credits for graduation. As many as 25-30 percent of student populations were enrolled in activity classes during any academic year and fitness courses have seen the greatest increase in popularity in recent years. Schoolsjustify this physical activity requirement with similar rationale. Responding institutions in the Hensley [3] study listed the following institutional goals for required physical activity classes: to facilitate lifelong participation in physical activity, to help students to enjoy physical activity, to provide students the opportunity to become fit and healthy, and to help students understand the importance of physical activity in their lives.

These are certainly commendable goals, if they are actually achieved. A 1997 study by Pearman, Valois, Sargent, Saunders, Drane, and Macera provided some support that they were [4]. This study examined the impact of a certain required college health and physical activity course on the subsequent health status of alumni and found positive effects. Alumni who had taken the class were more aware of their blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and recommended dietary fat intake and were more likely to be involved in aerobic physical activity, less likely to smoke, and more aware of good eating habits after they graduated. Also, Roberts [5} reported that 89% of fitness students and 86% of skill sport students in his study indicated that they were likely or very likely to continue to be engaged in their activity after completion of the class. Even 65% of alumni who had taken the required courses reported that they continued to exercise for at least two days each week and 55.5% responded that taking the physical activity classes in college had a positive influence on their current exercise habits. This finding again supported the concept that behavior patterns concerning physical activity which are developed in earlier life may last into later life.

Like most human experiences, each student in a physical activity class approaches the course with a different level of skill and knowledge, and, perhaps,a very different expectation as to what is to be gained from the class. Some students, of course, may see the class as simply an unpleasant requirement with the goal of successfully earning the credit to move on. Others, with minimal knowledge and skill, may hope to gain some basic understanding in a particular sports activity by taking the class. Yet others with more advanced knowledge and skill may expect to sharpen their game and gain some additional competitive edge. Probably all have some individual expectations when signing up for the class, but there is really little way for them to know in advance whether any of these will be met. The expectations of some may be unreasonable and remain unfulfilled at the end of the class.

Research literature dealing with this specific topic of required physical activity classes is limited to date. In a dissertation study, Chen [6] focused on the motivations of college students for taking physical activity classes, but did not actually evaluate students’ expectations or whether they were being met. The study also examined the impact of demographic factors in relation to motivation, the relative importance of the various motivational components, and how motivational components impacted such things as participation, attendance, and student effort. In contrast to the proposed study, this prior study used a standard motivation questionnaire and 491 students responded and completed the survey at the beginning of the semester. A follow-up questionnaire was completed by 264 students in the ninth and tenth weeks of the semester and a final questionnaire was completed by 355 students at the end of the semester.

Chen [6] found that the most important motivational component was “enjoyment”, followed in importance by “learning”, challenge”, “improvement”, “physical”, and “social”. However, a difference was found between students who were skill-oriented and those who were fitness-oriented. That is, skill-oriented students were motivated by “learning” and “enjoyment”, but “physical” and “improvement” were the most important motivators for fitness-oriented students. No relationships were found between any motivational component and either intentionto attend or actual attendance. Effort intention was found to be significantly influenced by “enjoyment”, “physical”, and “learning”, whereas self-evaluation was influenced by “enjoyment” and “challenge”.

Other, somewhat different, research examined the relationship between student motivation and participation in physical activity in general, but not necessarily in a class setting. Some of the more recent relevant work has been published as a dissertation [7] and as a research article [1]. The dissertation study by Delong [7] examined the motivations of 277 college students to be physically active at a small private college. The study used an online survey to consider the effects of motivation, self-determination, stage of change in behavior (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance), self-efficacy (belief in one’s self to complete a task), decisional balance (the pros and cons of the activity), and leisure time activity. Activity levels were found to vary across the stages of change and, primarily, participants became more self-determined as they progressed through the stages. Self-efficacy was found to be lower during the early stages of pre- contemplation and contemplation and decisional balance was higher during preparation, action, and maintenance. The conclusion was that the present approaches in required courses may not increase the physical activity level among college students.

Pauline [1] recently examined physical activity behaviors among college students, but also not in a class setting. This study utilized two questionnaires to determine the existing physical activity behaviors, motivation factors, and self-efficacy levels among 871 undergraduate students. The goal was to use this information to develop tailored physical activity programs and interventions for the targeted students. Differences were found between male and female students. Males were primarily motivated by performance and ego factors and showed higher levels of coping and scheduling self-efficacy (greater ability to still participate in physical activity even when stressed by situation or time). In contrast, females were primarily motivated by aesthetic and health factors such as weight management, physical appearance, stress management, good health, and nimbleness. These data suggested the need to consider gender when developing physical activity interventions for college students. Again, this study was not conducted in a class setting and did not consider student expectations or whether they were being met.

Roberts [5] presented a case study in which current and former students at a four-year university were questioned concerning their experiences with the required two-credit physical activity classes. The study focused on the extent to which physical activity class objectives were met. the findings of this study suggested that course objectives were being met in several specific ways. First, the fitness and skill of students were increased by taking the classes. Second, students had a good attitude about the classes going into them and a better attitude toward them upon completion. Finally, positive motivation of the students was demonstrated by the continuing physical activity among alumni who had taken the classes. It should be noted that this particular study focused on the goals of institution and not on the goals of the individuals taking the class.

The purpose of this study was to examine the specific expectations of students engaged in required physical activity classes, not only to determine what the expectations were, but also to see if they were being met. Motivations, of course, may differ from expectations. Motivations may be defined as “the act or process of giving someone a reason to do something” [8] and expectations defined as “a belief that something will happen or is likely to happen” [9]. This basic qualitative study examined student expectations through short interviews. The results of this study may help to inform physical education departments and teaching assistants in understanding and addressing different student expectations and may also suggest ways in which to improve course descriptions and content.

The proposed work was conducted as a basic qualitative study and gathered the impressions and expectations of college students engaged in required physical activity classes. The phenomenological approach has been widely used “to depict the essence or basic structure of experience” and uses in-depth interview as the research tool [10]. Student expectations may vary as widely as the number of study participants and uncovering and understanding them will best be determined through the use of open-ended questions during interviews.Several fundamental questions were addressed in this study. First, what are students’ opinions concerning physical activity in general? Second, are the students involved in independent physical activity? Third, what are students’ expectations of required physical activity classes? Fourth, are those expectations being met to the satisfaction of the students? Finally, what suggestions do students have for improving required physical activity classes?

Ii. Method

2.1Design

For this study, I used a basic qualitative design generally falling within the phenomenological approach and with an interpretivist theoretical framework perspective. Interpretivism implies that reality is relative to the individual. Additionally, constructivism was the underlying epistemological idea and states that reality is constructed between the interactions of one’s social world [11]. This basic classical approach was appropriate for the intended purpose in the present study.

2.2Participants

Following Institutional Review Board approval, eight student participants were recruited from physical activity classes being currently taught by the principal investigator. The study was briefly outlined in class and interested students could volunteer for consideration to be participants. It was clearly stated that participation is voluntary, that no additional credit would be given for participation, and that no negative consequences would result from non-participation or from the responses provided during the interviews. Student participants were required to understand, agree to, and sign a consent document to participate in the study.Two students (one novice and the other with more advanced skill and knowledge of the class sport) were selected from each of two sections of a bowling class and two students from each of two sections of a volleyball class. This selection based on skill level was to provide a possible difference in perspective and/or expectations.

2.3Data Collection

Participants were individually interviewed. Interviews were semi-structured, lasted about 10 to 15 minutes, and were conducted outside of class in the office of the principal investigator at a mutually-convenient time. The initial interviews consisted of a series of appropriate open-ended questions concerning student expectations of the particular course and whether they are being met to the satisfaction of each student. Responses determined the need for subsequent interviews with additional questions. None was required. The interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed for evaluation by the principal investigator. Each transcribed interview was returned to the participant for verification and/or clarification of content before being used.

2.4Data Analysis

Data analysis was patterned after the method described by Colaizzi [12] in which the transcribed interviews were studied to gain a general feeling for the nature of the responses. Significant or repeated comments or phrases, if any, in response to the target questions were taken from the responses and these were grouped into similar themes. These themes were used to develop additional interview questions if necessary and also used to develop a comprehensive description of the participants’ experiences.

III. FINDINGS

3.1 Students’ Comments Concerning Physical Activity in General

The first fundamental question considered in this study concerned students’ opinions of physical activity in general. All of the participants, regardless of gender or specific sport activity, spoke in favor of physical activity being a positive for all college students. The typical rationale was that physical activity was good for keeping mental focus, for feeling better, for being healthy, or to increase cognitive ability. All participants expressed satisfaction and enjoyment concerning their physical activity classes whether they were currently taking them or had taken them in the past. This finding of student satisfaction with activity classes was also supported by Roberts [5], who also reported that students had a good attitude going into activity classes and an even better attitude upon completion. Tyler, a freshman communication major with some prior outdoor physical activity class experience at a community college, summed it up by saying:

It keeps me focused. Makes you feel better. Every college student should give it a shot.

Janet, a senior psychology major, also emphasized the potential health benefits and responded:

I think that it’s very important, especially because college is very stressful and exercise helps relieve some of the stress and helps your health quite a bit.

A slightly different approach was applied by Alicia, a senior majoring in nutrition. She emphasized both the psychological and the physiological benefits of regular exercise:

I think that it’s definitely important that college students try and incorporate some physical activity into their day. I mean, I’ve read research that indicates that physical activity helps with depression and stress and it’s also good in the nutrition aspects of things because if somebody is like trying to lose weight or something, they can’t just diet. Like, they need to couple it with physical activity to kind of speed up that metabolism. So, I think that all college students should try to incorporate some into their daily routine.

Although all of the participants supported the importance of regular physical activity, it was interesting that most were personally not involved in an independent regular physical activity program, other than the current required activity course. The exceptions were a single female student who had a regular running program and a single male student who was a member of the university football team, but was injured and on in- active status. The students’ eager support for the concept of regular physical activity and their lack of execution suggested the old adage of “do as I say and not as I do”. The students who were not involved in an independent regular physical activity program gave no particular reasons for their inactivity and apparently did not see the contradiction in their statements.

3.2 Students’ Comments Concerning Requiring Physical Activity Classes for Graduation

A second major question in the study was centered upon the students’ opinions concerning the requiring of several physical activity classes for them to graduate. The standard university requirement is four, one-credit activity courses of the student’s choice. In some universities the required activity courses are simply pass-fail, but in many universities they result in a letter-grade.

One interesting observation among the student participants in this study was that most were not aware, or apparently had not even considered, that physical activity courses were actually a required part of their curriculum and necessary for graduation. Janet’s comment reflected the typical lack of understanding:

I think that it would be good for it to be a requirement just so that you get people involved. You know, it is nice that they have the option in what they can take.

Regardless of whether the students were aware of the requirement, there was strong support for the concept. The student rationale for requiring activity classes ranged from learning how to use exercise machines, the social aspects of taking such classes, forcing students to be physically active for at least some portion of their life, moving students out of their typical comfort zone, reducing stress, and enhancing cognition. Dan, a senior majoring in business administration, even went further in his support of the idea:

Like I said, I think that it’s great. A good thing for sure. It’s necessary as well. I think that it should be required to have one every semester, honestly. But, uh, I think that it’s very good, very beneficial for students.

Finally, Tyler had a more basic approach to the concept of requiring physical activity classes:

I think that’s great. I would rather take physical activity classes because anything physical is way “funner” than anything mental. So, I think that’s fine.

The conclusion was that regardless of the student’s knowledge or awareness of the requirement for physical activity courses, they were all supportive of the concept. None made any negative comments concerning the requirement. The general student perception was that required physical activity classes provide something beneficial

3.3 Students’ Comments Concerning Class Expectations

The third major question in this study concerned the specific nature of students’ expectations of physical activity classes. That is, did they have any preconceived notions of what they actually wanted to get out of any particular activity class? Opinions varied somewhat, but, in general, theirexpectations were not very high. Student expectations included just wanting to be physically active and sweat, the social prospects that such classes could afford, learning the basics of the particular physical activity, and personal physical goals. Interestingly, there were no clear differences in expectations between genders or relating to any prior experience with the particular physical activity. Jenny’s expectations were only physical, as she expressed:

I expect to get a moderate amount of exercise, which with volleyball, I do. I definitely work up a sweat which is nice.

Janet expressed the expectations of several other students in the following way: I expected to learn and to gain knowledge about the sport.

Lynn, in contrast, explained that her goals changed with the differentclasses:

The answer depends on what kind of class. There is always a different goal for each different class, I guess, so…it depends.

The dissertation study by Chen [6] also confirmed that “physical”, “improvement”, and “social” were important, but not the most important, factors motivating students in required physical activity classes

3.4 Meeting Students’ Expectations

The fourth major question in the study involved whether students’ expectations were actually being met in physical activity classes. Were they satisfied with what they got out of the classes? Given that the expectations were not actually very high, it may not be surprising to find that all of the students expressed satisfaction with what they gained from the classes. This satisfaction was expressed in several different ways, but the conclusions were generally the same. Janet’s response was representative of the entire group of participants concerning whether her expectations for the class had been met:

Ah, yes. I learned quite a bit and it was enjoyable at the same time. So, I mean, that’s important.

Janet’s expression of enjoyment as an expectation (or goal) was supported in a dissertation study by Chen [6]. Chen also found that “enjoyment” was the most important motivator for college students talking required physical activity courses. Also in support of Janet’s comments, Chen reported “learning” as the second most important motivator.

3.5 Students’ Recommendations

At the end of the interview, each student participant was given the opportunity to make suggestions concerning how physical activity classes could be improved. These suggestions included starting each class session with a short lecture about sport rules, basic technique, or simply an outline of the activities for the class period. Tyler even expressed his approval of having an occasional short examination to start the class:

I kind of like the tests. I never had tests in a physical activity class before and they are not hard tests. They are tests that help understand the sport more and I think that’s a good idea.

Other students suggested that classes be divided into those students with more experience in the particular activity in one group and beginners in another group. Lynn suggested the following activity class arrangement:

…when I was at….I took PE classes there also and they had like a beginner level and they had like the more competitive and I think that was really great. I think that would be really great to have.

This particular concept has also been studied and suggested in research by Drylund and Wininger [13] involving cognitive evaluation theory and exercise attendance.These researchers also suggested that dividing participants into groups of similar skill level would increase feelings of competence and relatedness among the individual members of the group. Participants would then not be intimated and made to feel less capable when compared to others having greater skill.

IV. DISCUSSION

Many college students likely feel that their lives are filled with the stresses of classroom activities, study, social life, and sleep deprivation and there is little spare time for regular physical activity. Studies, however, have shown the beneficial effects of regular physical activity on both mental and physical well-being and the activity requirements to achieve those benefits [2]. Many colleges and universities do their small part in encouraging at least some regular physical activity among students by requiring a series of physical activity classes for graduation. In this regard, the study by Pearman [4] examined the relationship between required a required health and physical education course and the subsequent health status of alumni. Even though this was not simply a physical activity course (but also included health topics), it demonstrated the link between behaviors set during earlier life having an impact on those in later life and a possible benefit of requiring such classes.

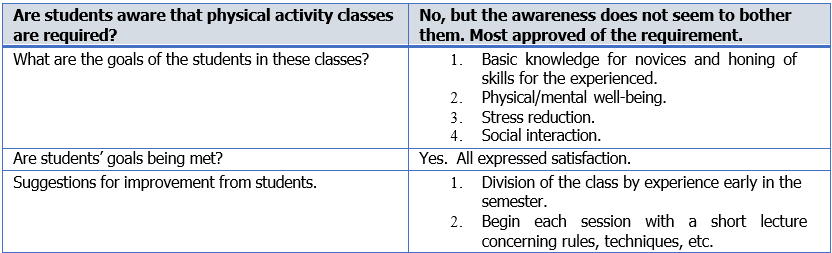

This study demonstrates the power of even the most basic qualitative research method in obtaining useful information from only a relatively small number of participants. Although consisting of only eight student participants, common themes in their responses were easily seen by the end of the interviews and saturation was accomplished. The findings of this study confirmed several points concerning students’ expectations of required physical activity courses and they are summarized in the following table:

All of the students in this study supported the idea that college students should be involved in regular physical activity. However, almost none of the same students were themselves involved in a regular, independent physical activity program. Almost all of the students interviewed seem to be unaware that physical activity courses were in fact required for their graduation. However, all of the students interviewed were supportive of physical activity courses being required. Students’ expectations concerning what they wanted to gain from physical activity classes were pretty basic. All of the students in this study were satisfied that their individual expectations of the courses had been met. Roberts [5] also found that students felt that course objectives had been met in several ways. Students who did not have certain levels of skill or fitness did so after completing the class. Finally, successful completion of the class translated into an alumni participation rate in physical activity of 65% as compared to the national average of only 35%.

The students in this study were very supportive of physical activity in general and also of required physical activity classes. These findings also support those of Hensley [3] who reported that students participating in the required physical activity courses did not do so reluctantly, but seemed to come to them with a positive attitude to enjoy them and to gain at least some health benefits. Roberts [5] also reported thatmost students had a good attitude upon entering the class and their attitude was even better at the end of the class. Requiring physical activity classes would seem to be justified based upon the positive responses by students in this study, the proven benefits to students while in college, and upon those health/exercise behaviors and benefits that may persist into adulthood.

Conclusion

Although the students were satisfied with their experience with required physical activity classes, most of the students had also thought enough about the classes to be able to offer some meaningful suggestions to improve them. Instructors may improve student enjoyment and satisfaction by providing a short orientation at the beginning of the class, by simply initially asking the class members what they would like to gain from the class, by providing basic instruction in rules and techniques, and by separating class members into beginner level and more advanced level for at least the initial portion of the semester.

This research may have been limited because the researcher was also the instructor for all of the students during the semester when the interviews were taken. However, participants were fully informed that participation was entirely voluntary and had no impact on their current grade. Also, the research was possibly limited to some extent by the relative small number of participants. Despite this, clear themes were still found among the responses from the student participants. By the end of the interviews, common themes were being repeated in response to the major questions and saturation had been achieved to the satisfaction of the researcher.

Future research may examine ways in which students may more effectively communicate their particular goals to instructors and communicate whether these are actually being met during the term of the class. Research may also focus on ways in which to make physical activity classes more enjoyable, while also being somewhat demanding, since these are important goals for the students who take them. Finally, research should be directed toward the apparent disconnect between students’ stated support for being physically active and the reality that most do not actually participate in a regular, independent exercise program outside of the required courses. Programs to encourage independent exercise are needed.

References

-

J.S. Pauline, Physical activity behaviors, motivation, and self-efficacy among college students. College Student Journal, 47(1), 2013, 64-74.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

W.L. Haskell, I. Lee, R.R. Pate, K. E. Powell, S.N. Blair, B. A Franklin, C. A. Macera, G.W. Heath, P.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

D. Thompson, and A. Bauman, Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendations for adults from the American College of Sport Medicine and the American Heart Association, Circulation, 116, 2007, 1081-1093.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

L.D. Hensley, Current status of basic instruction programs in physical education at American colleges and universities, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 71(9), 2000, 30-36.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

S.N. Pearman, R.F. Valois, R.G. Sargent, R.P. Saunders, J.W. Drane, and C.A. Macera, The impact of a required college health course and physical education course on the health status of alumni, Journal of American College Health, 46(2), 1997, 77-85.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

T.C. Roberts, Student feedback in assessment of college/university instructional physical activity programs, LAHPERD Journal, 75(1), 2011, 6-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

J. Chen, College students’ motivation for taking physical activity classes, doctoral diss., The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Dissertation Abstracts International, 61(07), 2000, 2590.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

L.L. DeLong, L.L. College students’ motivation for physical activity, doctoral diss., Louisiana State University, Dissertation Abstracts International, 67(12), 2006.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Motivations, Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved September 23, 2014, from www.merriam- webster.com/dictionary/motivations.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Expectations, Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved September 23, 2014, from www.merriam- webster.com/dictionary/expectations.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

S.B. Merriam, S.B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009).

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

J.W. Creswell, Qualitative inquiry & research design (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007).

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

P.R. Colaizzi, Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it, in R. Valle & M. King (Eds.), Existential phenomenological alternatives in psychology, (New York: Oxford University Press 1978) 48-71.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

A.K. Dyrlund, and S. R Wininger, An evaluation of barrier efficacy and cognitive evaluation theory as predictors of exercise attendance, Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 11, 2006, 133-146.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar