Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/BRCA-RA-25-017

Chronic Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura May Even Prolong Survival in Human Being in General

Abstract

Abstract:

Background: Atherosclerosis may be the major cause of aging and death, and the role of platelets (PLT) is well-known in the terminal consequences of atherosclerosis.

Methods: All patients with sickle cell diseases (SCD) were included.

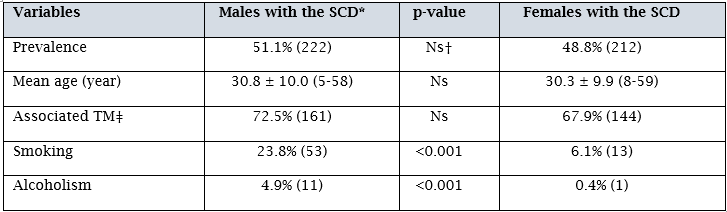

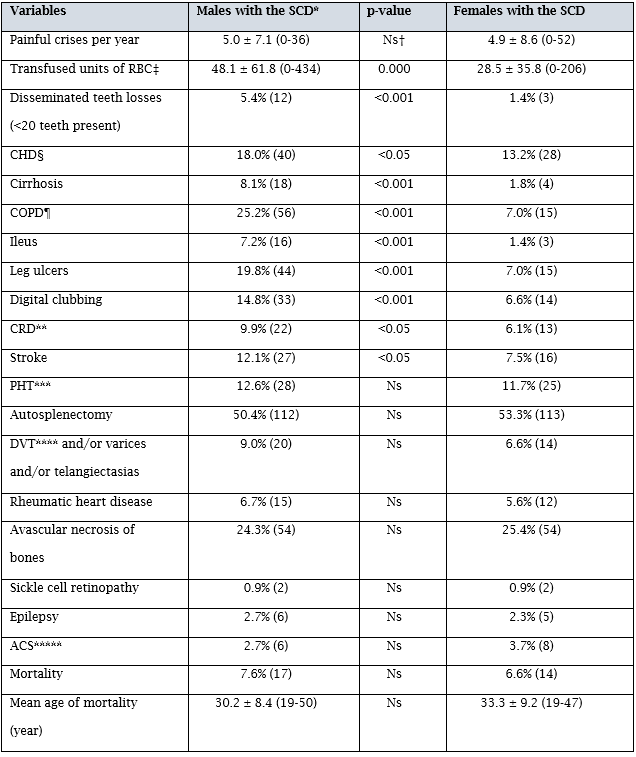

Results: We studied 222 males and 212 females with similar ages (30.8 vs 30.3 years, p>0.05, respectively). Smoking (23.8% vs 6.1%, p<0.001), alcohol (4.9% vs 0.4%, p<0.001), transfused red blood cells (RBC) in their lives (48.1 vs 28.5 units, p=0.000), disseminated teeth losses (5.4% vs 1.4%, p<0.001), ileus (7.2% vs 1.4%, p<0.001), coronary heart disease (CHD) (18.0% vs 13.2%, p<0.05), cirrhosis (8.1% vs 1.8%, p<0.001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (25.2% vs 7.0%, p<0.001), leg ulcers (19.8% vs 7.0%, p<0.001), clubbing (14.8% vs 6.6%, p<0.001), chronic renal disease (9.9% vs 6.1%, p<0.05), and stroke (12.1% vs 7.5%, p<0.05) were all higher in males, significantly.

Conclusion: As a prototype of accelerated atherosclerosis, hardened RBC-induced capillary endothelial damage initiating at birth terminates with multiorgan failures in much earlier ages in the SCD. Excess fat tissue may be much more important than smoking and alcohol for atherosclerosis, and CHD and stroke may be the terminal causes of death in both genders at the moment. Although the possibility of some severe bleedings in rare cases, we have just seen two mortile cases due to the chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in our 25 years of experience. Due to the well-known roles of PLT during the terminal atherosclerotic consequences, chronic ITP may even prolong the survival in human being in general.

Introduction

Chronic endothelial damage may be the main cause of aging and death by causing multiorgan failures in human being at the moment (1). Much higher blood pressures (BP) of the afferent vasculature may be the major accelerating factor by causing recurrent injuries on vascular endothelium. Probably, whole afferent vasculature including capillaries are chiefly affected in the process. Therefore the term of venosclerosis is not as famous as atherosclerosis in the literature. Due to the chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, and fibrosis, vascular walls thicken, their lumens narrow, and they lose their elastic natures, those eventually reduce blood supply to the terminal organs, and increase systolic and decrease diastolic BP further. Some of the well-known accelerating factors of the inflammatory process are physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, emotional stress, animal-rich diet, smoking, alcohol, overweight, chronic inflammations, prolonged infections, and cancers for the development of terminal consequences including obesity, hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary heart disease (CHD), cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic renal disease (CRD), stroke, peripheric artery disease (PAD), mesenteric ischemia, osteoporosis, dementia, early aging, and premature death (2, 3). Although early withdrawal of the accelerating factors can delay terminal consequences, after development of obesity, HT, DM, cirrhosis, COPD, CRD, CHD, stroke, PAD, mesenteric ischemia, osteoporosis, and dementia-like end-organ insufficiencies and aging, the endothelial changes can not be reversed, completely due to their fibrotic natures. The accelerating factors and terminal consequences of the vascular process are researched under the titles of metabolic syndrome, aging syndrome, and accelerated endothelial damage syndrome in the literature (4-6). On the other hand, sickle cell diseases (SCD) are chronic inflammatory and highly destructive processes on vascular endothelium, initiated at birth and terminated with an accelerated atherosclerosis-induced multiorgan insufficiencies in much earlier ages (7, 8). Hemoglobin S causes loss of elastic and biconcave disc shaped structures of red blood cells (RBC). Probably loss of elasticity instead of shape is the main problem since sickling is rare in peripheric blood samples of the cases with associated thalassemia minors (TM), and human survival is not affected in hereditary spherocytosis or elliptocytosis. Loss of elasticity is present during whole lifespan, but exaggerated with inflammations, infections, and additional stresses of the body. The hardened RBC-induced chronic endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, and fibrosis terminate with tissue hypoxia all over the body (9). As a difference from other causes of chronic endothelial damage, SCD keep vascular endothelium particularly at the capillary level (10, 11), since the capillary system is the main distributor of the hardened RBC into the tissues. The hardened RBC-induced chronic endothelial damage builds up an accelerated atherosclerosis in much earlier ages. Vascular narrowings and occlusions-induced tissue ischemia and multiorgan insufficiencies are the final consequences, so the mean life expectancy is decreased by 25 to 30 years in both genders in the SCD (8).

Material and methods

The study was performed in Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University between March 2007 and June 2016. All patients with the SCD were included. The SCD were diagnosed with the hemoglobin electrophoresis performed via high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Medical histories including smoking, alcohol, acute painful crises per year, transfused units of RBC in their lives, leg ulcers, stroke, surgical operations, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), epilepsy, and priapism were learnt. Patients with a history of one pack-year were accepted as smokers, and one drink-year were accepted as drinkers. A complete physical examination was performed by the Same Internist, and patients with disseminated teeth losses (<20>

Results

The study included 222 males and 212 females with similar ages (30.8 vs 30.3 years, p>0.05, respectively), and there was no patient above the age of 59 years in both genders. Prevalences of associated TM were similar in both genders, too (72.5% vs 67.9%, p>0.05, respectively). Smoking (23.8% vs 6.1%) and alcohol (4.9% vs 0.4%) were higher in males (p<0>

Transfused units of RBC in their lives (48.1 vs 28.5, p=0.000), disseminated teeth losses (5.4% vs 1.4%, p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>p<0>

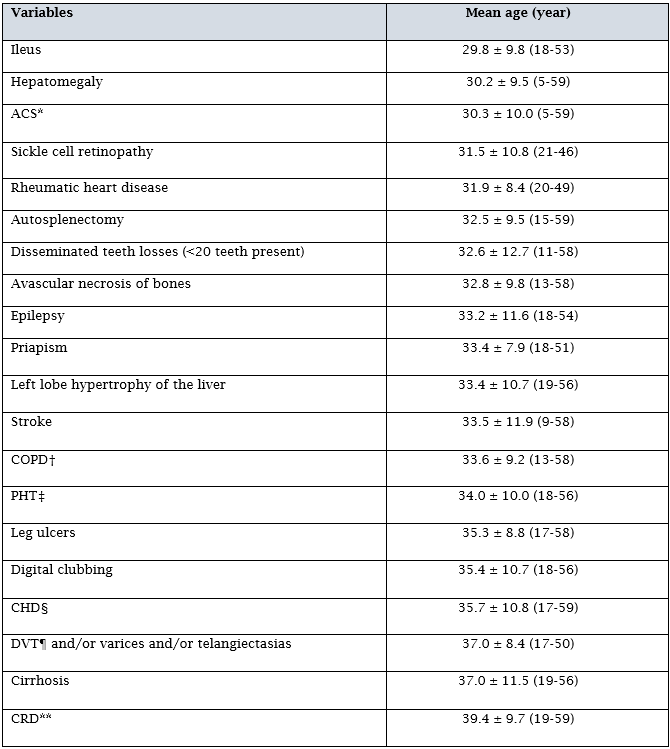

On the other hand, mean ages of the other atherosclerotic consequences in the SCD were shown in Table 3.

*Acute chest syndrome †Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ‡Pulmonary hypertension §Coronary heart disease ¶Deep venous thrombosis **Chronic renal disease

Discussion

Excess weight may be the most common cause of disseminated vasculitis all over the world at the moment, and it may be one of the terminal endpoints of the metabolic syndrome, since after development of excess weight, nonpharmaceutical approaches provide limited benefit either to improve excess weight or to prevent its complications. Excess fat tissue may lead to a chronic and low-grade inflammation on vascular endothelium, and risk of death from all causes including cardiovascular diseases and cancers increases parallel to the range of excess fat tissue in all age groups (19). The low-grade chronic inflammation may also cause genetic changes on the epithelial cells, and the systemic atherosclerotic process may decrease clearance of malignant cells by the immune system, effectively (20). Excess fat tissue is associated with many coagulation and fibrinolytic abnormalities suggesting that it causes a prothrombotic and proinflammatory state (21). The chronic inflammatory process is characterized by lipid-induced injury, invasion of macrophages, proliferation of smooth muscle cells, endothelial dysfunction, and increased atherogenicity (22, 23). For example, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in serum carry predictive power for the development of major cardiovascular events (24, 25). Overweight and obesity are considered as strong factors for controlling of CRP concentration in serum, since fat tissue produces biologically active leptin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and adiponectin-like cytokines (26, 27). On the other hand, individuals with excess fat tissue will have an increased circulating blood volume as well as an increased cardiac output, thought to be the result of increased oxygen demand of the excess fat tissue. In addition to the common comorbidity of atherosclerosis and HT, the prolonged increase in circulating blood volume may lead to myocardial hypertrophy and decreased compliance. Beside the systemic atherosclerosis and HT, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and serum cholesterol increased and high density lipoproteins (HDL) decreased with increased body mass index (BMI) (28). Similarly, the prevalences of CHD and stroke, particularly ischemic stroke, increased parallel with the elevated BMI values in another study (29). Eventually, the risk of death from all causes including cardiovascular diseases and cancers increased throughout the range of moderate and severe excess fat tissue for both genders in all age groups (30). The excess fat tissue may be the most common cause of accelerated atherosclerotic process all over the body at the moment, the individuals with underweight may even have lower biological ages (30). Similarly, calorie restriction extends lifespan and retards age-related chronic diseases (31).

Smoking may be the second most common cause of disseminated vasculitis all over the world at the moment. It may cause a systemic inflammation on vascular endothelium terminating with an accelerated atherosclerosis-induced multiorgan insufficiencies in whole body (32). Its atherosclerotic effect is the most obvious in the COPD and Buerger’s disease (33). Buerger’s disease is an obliterative vasculitis characterized by inflammatory changes in the small and medium-sized arteries and veins, and it has never been documented in the absence of smoking. Its characteristic findings are acute inflammation, stenoses and occlusions of arteries and veins, and involvements of hands and feet. It is usually seen in young males between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Claudication may be the most common initial symptom in Buerger's disease. It is an intense pain caused by insufficient blood flow during exercise in feet and hands but it may even develop at rest in severe cases. It typically begins in extremities but it may also radiate to more central areas in advanced cases. Numbness or tingling of the limbs is also common. Raynaud's phenomenon may also be seen in which fingers or toes turn a white color upon exposure to cold. Skin ulcerations and gangrene of fingers or toes are the final consequences. Gangrene of fingertips may even need amputation. Unlike many other forms of vasculitis, Buerger's disease does not keep other organs with unknown reasons, yet. Similar to the venous ulcers, diabetic ulcers, leg ulcers of the SCD, digital clubbing, onychomycosis, and delayed wound and fracture healings of the lower extremities, pooling of blood due to the gravity may be important in the development of Buerger's disease, particularly in the lower extremities. Angiograms of upper and lower extremities are diagnostic for Buerger's disease. In angiogram, stenoses and occlusions in multiple areas of arms and legs are seen. In order to rule out some other forms of vasculitis by excluding involvement of vascular regions atypical for Buerger's disease, it is sometimes necessary to perform angiograms of other body regions. Skin biopsies are rarely required, since a biopsy site near a poorly perfused area will not heal, completely. Association of Buerger's disease with tobacco use, particularly cigarette smoking is clear. Although most patients are heavy smokers, some cases with limited smoking history have also been reported. The disease can also be seen in users of smokeless tobacco. The limited smoking history of some patients may support the hypothesis that Buerger's disease may be an autoimmune reaction triggered by some constituent of tobacco. Although the only treatment way is complete cessation of smoking, the already developed stenoses and occlusions are irreversible. Due to the clear evidence of inflammation in this disorder, anti-inflammatory dose of aspirin plus low-dose warfarin may probably be effective to prevent microvascular infarctions in fingers or toes at the moment. On the other hand, FPG and HDL may be negative whereas triglycerides, low density lipoproteins (LDL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein may be positive acute phase reactants indicating such inflammatory effects of smoking on vascular endothelium (34). Similarly, it is not an unexpected result that smoking was associated with the lower values of BMI due to the systemic inflammatory effects on vascular endothelium (35). In another definition, smoking causes a chronic inflammation in human body (36). Additionally, some evidences revealed an increased heart rate just after smoking even at rest (37). Nicotine supplied by patch after smoking cessation decreased caloric intake in a dose-related manner (38). According to an animal study, nicotine may lengthen intermeal time, and decrease amount of meal eaten (39). Smoking may be associated with a postcessation weight gain, but the risk is the highest during the first year, and decreases with the following years (40). Although the CHD was detected with similar prevalences in both genders, prevalences of smoking and COPD were higher in males against the higher prevalences of white coat hypertension, BMI, LDL, triglycerides, HT, and DM in females (41). Beside that the prevalence of myocardial infarction is increased three-fold in men and six-fold in women who smoked at least 20 cigarettes per day (42). In another word, smoking may be more dangerous for women about the atherosclerotic endpoints probably due to the higher BMI in them. Several toxic substances found in the cigarette smoke get into the circulation, and cause the vascular endothelial inflammation in various organ systems of the body. For example, smoking is usually associated with depression, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic gastritis, hemorrhoids, and urolithiasis in the literature (43). There may be several underlying mechanisms to explain these associations (44). First of all, smoking may have some antidepressant properties with several potentially lethal side effects. Secondly, smoking-induced vascular endothelial inflammation may disturb epithelial functions for absorption and excretion in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts which may terminate with urolithiasis, loose stool, diarrhea, and constipation. Thirdly, diarrheal losses-induced urinary changes may even cause urolithiasis (45). Fourthly, smoking-induced sympathetic nervous system activation may cause motility problems in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts terminating with the IBS and urolithiasis. Eventually, immunosuppression secondary to smoking-induced vascular endothelial inflammation may even terminate with the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tract infections causing loose stool, diarrhea, and urolithiasis, because some types of bacteria can provoke urinary supersaturation, and modify the environment to form crystal deposits in the urine. Actually, 10% of urinary stones are struvite stones which are built by magnesium ammonium phosphate produced during infections with the bacteria producing urease. Parallel to the results above, urolithiasis was detected in 17.9% of cases with the IBS and 11.6% of cases without in the other study (p<0>

CHD, together with the stroke, may be the terminal causes of death in every body with every disease for both sexes all over the world at the moment. The most common triggering event is the disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque in an epicardial coronary artery, which leads to a clotting cascade. The plaque is a gradual and unstable collection of lipids, fibrous tissue, and white blood cells (WBC), particularly the macrophages in arterial wall in decades. Stretching and relaxation of arteries with each heart beat increases mechanical shear stress on atheromas to rupture. After the myocardial infarction, a collagen scar tissue forms in its place. This scar tissue may also cause potentially life threatening arrhythmias since the injured heart tissue conducts electrical impulses more slowly than the normal heart tissue. The difference in conduction velocity between the injured and uninjured tissue can trigger re-entry or a feedback loop that is believed to be cause of many lethal arrhythmias. Ventricular fibrillation is the most serious arrhythmia that is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death. It is an extremely fast and chaotic heart rhythm. Another life threatening arrhythmia is ventricular tachycardia that may also cause sudden cardiac death. Ventricular tachycardia usually results in rapid heart rates which prevent effective pumping. Cardiac output and blood pressure may fall to dangerous levels which can lead to further coronary ischemia and extension of infarct. This scar tissue may even cause ventricular aneurysm, rupture, and sudden death. Physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, emotional stress, animal-rich diet, excess fat tissue, smoking, alcohol, chronic infection and inflammations, and cancers are important in atherosclerotic plaque formation in time. Physical inactivity is important since moderate physical exercise is associated with a 50% reduced incidence of CHD (46). Probably, excess fat tissue may be the most important cause of CHD. There are approximately 20 kg of excess fat tissue between the lower and upper borders of normal weight, 35 kg between the lower borders of normal weight and obesity, 66 kg between the lower borders of normal weight and morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2), and 81 kg between the lower borders of normal weight and super obesity (BMI ≥ 45 kg/m2) in adults. In fact, there is a significant percentage of adults with a heavier fat mass than their organ plus muscle masses in their bodies. This excess fat tissue brings a heavy stress on liver, lungs, kidneys, brain, and of course on the heart.

Cirrhosis was the 10th leading cause of death for men and the 12th for women in the United States in 2001 (6). Although the improvements of health services worldwide, the increased morbidity and mortality of cirrhosis may be explained by prolonged survival of the human being, and increased prevalence of excess fat tissue all over the world. For example, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) affects up to one third of the world population, and it became the most common cause of chronic liver disease even at childhood, nowadays (47). NAFLD is a marker of pathological fat deposition combined with a low-grade inflammation which results with hypercoagulability, endothelial dysfunction, and an accelerated atherosclerosis (47). Beside terminating with cirrhosis, NAFLD is associated with higher overall mortality rates as well as increased prevalences of cardiovascular diseases (48). Authors reported independent associations between NAFLD and impaired flow-mediated vasodilation and increased mean carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) (49). NAFLD may be considered as one of the hepatic consequences of the metabolic syndrome and SCD (50). Probably smoking also takes role in the inflammatory process of the capillary endothelium in liver, since the systemic inflammatory effects of smoking on endothelial cells is well-known with Buerger’s disease and COPD (39). Increased oxidative stress, inactivation of antiproteases, and release of proinflammatory mediators may terminate with the systemic atherosclerosis in smokers. The atherosclerotic effects of alcohol is much more prominent in hepatic endothelium probably due to the highest concentrations of its metabolites there. Chronic infectious or inflammatory processes and cancers may also terminate with an accelerated atherosclerosis in whole body (51). For instance, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection raised CIMT, and normalization of hepatic function with HCV clearance may be secondary to reversal of favourable lipids observed with the chronic infection (51, 52). As a result, cirrhosis may also be another atherosclerotic consequence of the SCD.

Acute painful crises are the most disabling symptoms of the SCD. Although some authors reported that pain itself may not be life threatening directly, infections, medical or surgical emergencies, or emotional stress are the most common precipitating factors of the crises (53). The increased basal metabolic rate during such stresses aggravates the sickling, capillary endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, tissue hypoxia, and multiorgan insufficiencies. So the risk of mortality is much higher during the crises. Actually, each crisis may complicate with the following crises by leaving significant sequelaes on the capillary endothelial system all over the body. After a period of time, the sequelaes may terminate with sudden multiorgan failures and death during a final acute painful crisis that may even be silent, clinically. Similarly, after a 20-year experience on such patients, the deaths seem sudden and unexpected events in the SCD. Unfortunately, most of the deaths develop just after the hospital admission, and majority of them are patients without hydroxyurea therapy (54, 55). Rapid RBC supports are usually life-saving for such patients, although preparation of RBC units for transfusion usually takes time. Beside that RBC supports in emergencies become much more difficult in terminal cases due to the repeated transfusions-induced blood group mismatch. Actually, transfusion of each unit of RBC complicates the following transfusions by means of the blood subgroup mismacth. Due to the significant efficacy of hydroxyurea therapy, RBC transfusions should be kept just for acute events and emergencies in the SCD (54, 55). According to our experiences, simple and repeated transfusions are superior to RBC exchange in the SCD (56, 57). First of all, preparation of one or two units of RBC suspensions in each time rather than preparation of six units or higher provides time to clinicians to prepare more units by preventing sudden death of such high-risk patients. Secondly, transfusions of one or two units of RBC suspensions in each time decrease the severity of pain, and relax anxiety of the patients and their relatives since RBC transfusions probably have the strongest analgesic effects during the crises (58). Actually, the decreased severity of pain by transfusions also indicates the decreased severity of inflammation all over the body. Thirdly, transfusions of lesser units of RBC suspensions in each time by means of the simple transfusions will decrease transfusion-related complications including infections, iron overload, and blood group mismatch in the future. Fourthly, transfusion of RBC suspensions in the secondary health centers may prevent some deaths developed during the transport to the tertiary centers for the exchange. Finally, cost of the simple and repeated transfusions on insurance system is much lower than the exchange that needs trained staff and additional devices. On the other hand, pain is the result of complex and poorly understood interactions between RBC, WBC, platelets (PLT), and endothelial cells, yet. Whether leukocytosis contributes to the pathogenesis by releasing cytotoxic enzymes is unknown. The adverse actions of WBC on endothelium are of particular interest with regard to the cerebrovascular diseases in the SCD. For example, leukocytosis even in the absence of any infection was an independent predictor of the severity of the SCD (59), and it was associated with the risk of stroke in a cohort of Jamaican patients (60). Disseminated tissue hypoxia, releasing of inflammatory mediators, bone infarctions, and activation of afferent nerves may take role in the pathophysiology of the intolerable pain. Because of the severity of pain, narcotic analgesics are usually required to control them (61), but according to our practice, simple and repeated RBC transfusions may be highly effective both to relieve pain and to prevent sudden death that may develop secondary to multiorgan failures on the chronic inflammatory background of the SCD.

Hydroxyurea may be the only life-saving drug for the treatment of the SCD. It interferes with the cell division by blocking the formation of deoxyribonucleotides by means of inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase. The deoxyribonucleotides are the building blocks of DNA. Hydroxyurea mainly affects hyperproliferating cells. Although the action way of hydroxyurea is thought to be the increase in gamma-globin synthesis for fetal hemoglobin (Hb F), its main action may be the suppression of leukocytosis and thrombocytosis by blocking the DNA synthesis in the SCD (62, 63). By this way, the chronic inflammatory and destructive process of the SCD is suppressed with some extent. Due to the same action way, hydroxyurea is also used in moderate and severe psoriasis to suppress hyperproliferating skin cells. As in the viral hepatitis cases, although presence of a continuous damage of sickle cells on the capillary endothelium, the severity of destructive process is probably exaggerated by the patients’ own WBC and PLT. So suppression of proliferation of them may limit the endothelial damage-induced edema, ischemia, and infarctions in whole body (64). Similarly, final Hb F levels in hydroxyurea users did not differ from their pretreatment levels (65). The Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea (MSH) studied 299 severely affected adults with the SCA, and compared the results of patients treated with hydroxyurea or placebo (66). The study particularly researched effects of hydroxyurea on painful crises, ACS, and requirement of blood transfusion. The outcomes were so overwhelming in the favour of hydroxyurea that the study was terminated after 22 months, and hydroxyurea was initiated for all patients. The MSH also demonstrated that patients treated with hydroxyurea had a 44?crease in hospitalizations (66). In multivariable analyses, there was a strong and independent association of lower neutrophil counts with the lower crisis rates (66). But this study was performed just in severe SCA cases alone, and the rate of painful crises was decreased from 4.5 to 2.5 per year (66). Whereas we used all subtypes of the SCD with all clinical severity, and the rate of painful crises was decreased from 10.3 to 1.7 per year (p<0>p<0>

Aspirin is a member of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, inflammation, and acute thromboembolic events. Although aspirin has similar anti-inflammatory effects with the other NSAID, it also suppresses the normal functions of PLT, irreversibly. This property causes aspirin being different from other NSAID, which are reversible inhibitors. Aspirin acts as an acetylating agent where an acetyl group is covalently attached to a serine residue in the active site of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme. Aspirin inactivates the COX enzyme, irreversibly, which is required for prostaglandins (PG) and thromboxanes (TX) synthesis. PG are the locally produced hormones with some diverse effects, including the transmission of pain into the brain and modulation of the hypothalamic thermostat and inflammation in the body. TX are responsible for the aggregation of PLT to form blood clots. In another definition, low-dose aspirin use irreversibly blocks the formation of TXA2 in the PLT, producing an inhibitory effect on the PLT aggregation during whole lifespan of the affected PLT (8-9 days). Since PLT do not have nucleus and DNA, they are unable to synthesize new COX enzyme once aspirin has inhibited the enzyme. The antithrombotic property of aspirin is useful to reduce the incidences of myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, and stroke (69). Heart attacks are caused primarily by blood clots, and low-dose of aspirin is seen as an effective medical intervention to prevent a second myocardial infarction (70). According to the literature, aspirin may also be effective in prevention of colorectal cancers (71). On the other hand, aspirin has some side effects including gastric ulcers, gastric bleeding, worsening of asthma, and Reye syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Due to the risk of Reye syndrome, the US Food and Drug Administration recommends that aspirin or aspirin-containing products should not be prescribed for febrile patients under the age of 12 years (72). Eventually, the general recommendation to use aspirin in children has been withdrawn, and it was only recommended for Kawasaki disease (73). Reye syndrome is a rapidly worsening brain disease (73). The first detailed description of Reye syndrome was in 1963 by an Australian pathologist, Douglas Reye (74). The syndrome mostly affects children, but it can only affect fewer than one in a million children a year (74). Symptoms of Reye syndrome may include personality changes, confusion, seizures, and loss of consciousness (73). Although the liver toxicity typically occurs in the syndrome, jaundice is usually not seen with it, but the liver is enlarged in most cases (73). Although the death occurs in 20-40% of affected cases, about one third of survivors get a significant degree of brain damage (73). The cause of Reye syndrome is unknown (74). It usually starts just after recovery from a viral infection, such as influenza or chicken pox. About 90% of cases in children are associated with an aspirin use (74, 75). Inborn errors of metabolism are also the other risk factors, and the genetic testing for inborn errors of metabolism became available in developed countries in the 1980s (73). When aspirin use was withdrawn for children in the US and UK in the 1980s, a decrease of more than 90% in rates of Reye syndrome was seen (74). Early diagnosis improves outcomes, and treatment is supportive. Mannitol may be used in cases with the brain swelling (74). Due to the very low risk of Reye syndrome but much higher risk of death, aspirin should be added both into the acute and chronic phase treatments with an anti-inflammatory dose in childhood in the SCD (76).

Warfarin is an anticoagulant, and first came into large-scale commercial use in 1948 as a rat poison. It was formally approved as a medication to treat blood clots in human being by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1954. In 1955, warfarin’s reputation as a safe and acceptable treatment was bolstred when President Dwight David Eisenhower was treated with warfarin following a massive and highly publicized heart attack. Eisenhower’s treatment kickstarted a transformation in medicine whereby CHD, arterial plaques, and ischemic strokes were treated and protected against by using anticoagulants such as warfarin. Warfarin is found in the List of Essential Medicines of WHO. In 2020, it was the 58th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States. It does not reduce blood viscosity but inhibits blood coagulation. Warfarin is used to decrease the tendency for thrombosis, and it can prevent formation of future blood clots and reduce the risk of embolism. Warfarin is the best suited for anticoagulation in areas of slowly running blood such as in veins and the pooled blood behind artificial and natural valves, and in blood pooled in dysfunctional cardiac atria. It is commonly used to prevent blood clots in the circulatory system such as DVT and pulmonary embolism, and to protect against stroke in people who have atrial fibrillation (AF), valvular heart disease, or artificial heart valves. Less commonly, it is used following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and orthopedic surgery. The warfarin initiation regimens are simple, safe, and suitable to be used in ambulatory and in patient settings (77). Warfarin should be initiated with a 5 mg dose, or 2 to 4 mg in the very elderly. In the protocol of low-dose warfarin, the target international normalised ratio (INR) value is between 2.0 and 2.5, whereas in the protocol of standard-dose warfarin, the target INR value is between 2.5 and 3.5 (78). When warfarin is used and INR is in therapeutic range, simple discontinuation of the drug for five days is usually enough to reverse the effect, and causes INR to drop below 1.5 (79). Its effects can be reversed with phytomenadione (vitamin K1), fresh frozen plasma, or prothrombin complex concentrate, rapidly. Blood products should not be routinely used to reverse warfarin overdose, when vitamin K1 could work alone. Warfarin decreases blood clotting by blocking vitamin K epoxide reductase, an ezyme that reactivates vitamin K1. Without sufficient active vitamin K1, clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X have decreased clotting ability. The anticlotting protein C and protein S are also inhibited, but to a lesser degree. A few days are required for full effect to occur, and these effects can last for up to five days. The consensus agrees that patient self-testing and patient self-management are effective methods of monitoring oral anticoagulation therapy, providing outcomes at least as good as, and possibly better than, those achieved with an anticoagulation clinic. Currently available self-testing/self-management devices give INR results that are comparable with those obtained in laboratory testing. The only common side effect of warfarin is hemorrhage. The risk of severe bleeding is low with a yearly rate of 1-3% (80). All types of bleeding may occur, but the most severe ones are those involving the brain and spinal cord (79). The risk is particularly increased once the INR exceeds 4.5 (80). The risk of bleeding is increased further when warfarin is combined with antiplatelet drugs such as clopidogrel or aspirin (81). But thirteen publications from 11 cohorts including more than 48.500 total patients with more than 11.600 warfarin users were included in the meta-analysis (82). In patients with AF and non-end-stage CRD, warfarin resulted in a lower risk of ischemic stroke (p= 0.004) and mortality (p<0>p>0.05) (82). Similarly, warfarin resumption is associated with significant reductions in ischemic stroke even in patients with warfarin-associated intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) (83). Death occured in 18.7% of patients who resumed warfarin and 32.3% who did not resume warfarin (p= 0.009) (83). Ischemic stroke occured in 3.5% of patients who resumed warfarin and 7.0% of patients who did not resume warfarin (p= 0.002) (83). Whereas recurrent ICH occured in 6.7% of patients who resumed warfarin and 7.7% of patients who did not resume warfarin without any significant difference in between (p>0.05) (83). On the other hand, patients with cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) those were anticoagulated either with warfarin or dabigatran had low risk of recurrent venous thrombotic events (VTE), and the risk of bleeding was similar in both regimens, suggesting that both warfarin and dabigatran are safe and effective for preventing recurrent VTE in patients with CVT (84). Additionally, an INR value of about 1.5 achieved with an average daily dose of 4.6 mg warfarin, has resulted in no increase in the number of men ever reporting minor bleeding episodes, although rectal bleeding occurs more frequently in those men who report this symptom (85). Non-rheumatic AF increases the risk of stroke, presumably from atrial thromboemboli, and long-term low-dose warfarin therapy is highly effective and safe in preventing stroke in such patients (86). There were just two strokes in the warfarin group (0.41% per year) as compared with 13 strokes in the control group (2.98% per year) with a reduction of 86% in the risk of stroke (p= 0.0022) (86). The mortality was markedly lower in the warfarin group, too (p= 0.005) (86). The warfarin group had a higher rate of minor hemorrhage (38 vs 21 patients) but the frequency of bleedings that required hospitalization or transfusion was the same in both group (p>0.05) (86). Additionally, very-low-dose warfarin was a safe and effective method for prevention of thromboembolism in patients with metastatic breast cancer (87). The warfarin dose was 1 mg daily for 6 weeks, and was adjusted to maintain the INR value of 1.3 to 1.9 (87). The average daily dose was 2.6 mg, and the mean INR was 1.5 (87). On the other hand, new oral anticoagulants had a favourable risk-benefit profile with significant reductions in stroke, ICH, and mortality, and with similar major bleeding as for warfarin, but increased gastrointestinal bleeding (88). Interestingly, rivaroxaban and low-dose apixaban were associated with increased risks of all cause mortality compared with warfarin (89). The mortality rate was 4.1% per year in the warfarin group, as compared with 3.7% per year with 110 mg of dabigatran and 3.6% per year with 150 mg of dabigatran (p>0.05 for both) in patients with AF in another study (90). On the other hand, infections, medical or surgical emergencies, or emotional stress-induced increased basal metabolic rate accelerates sickling, and an exaggerated capillary endothelial edema-induced myocardial infarction or stroke may cause sudden deaths in the SCD (91). So lifelong aspirin with an anti-inflammatory dose plus low-dose warfarin may be a life-saving treatment regimen even at childhood both to decrease severity of capillary endothelial inflammation and to prevent thromboembolic complications in the SCD (92).

COPD is the third leading cause of death with various underlying etiologies in whole world (93, 94). Aging, physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, animal-rich diet, smoking, alcohol, male gender, excess fat tissue, chronic inflammations, prolonged infections, and cancers may be the major underlying causes. Atherosclerotic effects of smoking may be the most obvious in the COPD and Buerger’s disease, probably due to the higher concentrations of toxic substances in the lungs and pooling of blood in the extremities. After smoking, excess fat tissue may be the most significant cause of COPD all over the world due to the excess fat tissue-induced systemic atherosclerotic process in whole body. After smoking and excess fat tissue, regular alcohol consumption may be the third leading cause of the systemic accelerated atherosclerotic process and COPD, since COPD was one of the most common diagnoses in alcohol dependence (95). Furthermore, 30-day readmission rates were higher in the COPD patients with alcoholism (96). Probably an accelerated atherosclerotic process is the main structural background of functional changes that are characteristics of the COPD. The inflammatory process of vascular endothelium is enhanced by release of various chemicals by inflammatory cells, and it terminates with an advanced fibrosis, atherosclerosis, and pulmonary losses. COPD may actually be the pulmonary consequence of the systemic atherosclerotic process. Since beside the accelerated atherosclerotic process of the pulmonary vasculature, there are several reports about coexistence of associated endothelial inflammation all over the body in COPD (25, 97). For example, there may be close relationships between COPD, CHD, PAD, and stroke (98). Furthermore, two-third of mortality cases were caused by cardiovascular diseases and lung cancers in the COPD, and the CHD was the most common cause in a multi-center study of 5.887 smokers (99). When the hospitalizations were researched, the most common causes were the cardiovascular diseases, again (99). In another study, 27% of mortality cases were due to the cardiovascular diseases in the moderate and severe COPD (100). On the other hand, COPD may be the pulmonary consequence of the systemic atherosclerotic process caused by the hardened RBC in the SCD (93).

Leg ulcers are seen in 10% to 20% of the SCD (101), and the ratio was 13.5% in the present study. Its prevalence increases with aging, male gender, and SCA (102). Similarly, its ratio was higher in males (19.8% vs 7.0%, p<0>p<0>

Digital clubbing is characterized by the increased normal angle of 165° between nailbed and fold, increased convexity of the nail fold, and thickening of the whole distal finger (105). Although the exact cause and significance is unknown, the chronic tissue hypoxia is highly suspected (106). In the previous study, only 40% of clubbing cases turned out to have significant underlying diseases while 60% remained well over the subsequent years (18). But according to our experiences, digital clubbing is frequently associated with the pulmonary, cardiac, renal, and hepatic diseases and smoking which are characterized with chronic tissue hypoxia (5). As an explanation for that hypothesis, lungs, heart, kidneys, and liver are closely related organs which affect their functions in a short period of time. On the other hand, digital clubbing is also common in the SCD, and its prevalence was 10.8% in the present study. It probably shows chronic tissue hypoxia caused by disseminated endothelial damage, inflammation, edema, and fibrosis at the capillary level in the SCD. Beside the effects of SCD, smoking, alcohol, cirrhosis, CRD, CHD, and COPD, the higher prevalence of digital clubbing in males (14.8% vs 6.6%, p<0>

CRD is also increasing all over the world that can also be explained by aging of the human being, and increased prevalence of excess weight all over the world (107). Aging, physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, animal-rich diet, excess fat tissue, smoking, alcohol, inflammatory or infectious processes, and cancers may be the major causes of the renal endothelial inflammation. The inflammatory process is enhanced by release of various chemicals by lymphocytes to repair the damaged endothelial cells of the renal arteriols. Due to the continuous irritation of the vascular endothelial cells, prominent changes develop in the architecture of the renal tissues with advanced atherosclerosis, tissue hypoxia, and infarcts (108). Excess fat tissue-induced hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, elevated BP, and insulin resistance may cause tissue inflammation and immune cell activation (109). For example, age (p= 0.04), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (p= 0.01), mean arterial BP (p= 0.003), and DM (p= 0.02) had significant correlations with the CIMT (107). Increased renal tubular sodium reabsorption, impaired pressure natriuresis, volume expansion due to the activations of sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin system, and physical compression of kidneys by visceral fat tissue may be some mechanisms of the increased BP with excess fat tissue (110). Excess fat tissue also causes renal vasodilation and glomerular hyperfiltration which initially serve as compensatory mechanisms to maintain sodium balance due to the increased tubular reabsorption (110). However, along with the increased BP, these changes cause a hemodynamic burden on the kidneys in long term that causes chronic endothelial damage (111). With prolonged excess fat tissue, there are increased urinary protein excretion, loss of nephron function, and exacerbated HT. With the development of dyslipidemia and DM in cases with excess fat tissue, CRD progresses much more easily (110). On the other hand, the systemic inflammatory effects of smoking on endothelial cells may also be important in the CRD (112). Although some authors reported that alcohol was not related with the CRD (112), various metabolites of alcohol circulate even in the blood vessels of the kidneys and give harm to the renal vascular endothelium. Chronic inflammatory or infectious processes may also terminate with the accelerated atherosclerosis in the renal vasculature (111). Although CRD is due to the atherosclerotic process of the renal vasculature, there are close relationships between CRD and other atherosclerotic consequences of the metabolic syndrome including CHD, COPD, PAD, cirrhosis, and stroke (113, 114). For example, the most common cause of death was the cardiovascular diseases in the CRD again (115). The hardened RBC-induced capillary endothelial damage in the renal vasculature may be the main cause of CRD in the SCD. In another definition, CRD may just be one of the several atherosclerotic consequences of the metabolic syndrome and SCD, again (116).

Stroke, together with the CHD, may be the terminal causes of death at the moment. Both of them develop as an acute thromboembolic event on the chronic atherosclerotic background in most of the cases. Aging, male gender, smoking, alcohol, excess fat tissue, chronic inflammations, prolonged infections, cancers, and emotional stresses may be the major accelerating causes of the systemic process. Stroke is also a common complication of the SCD (117). Similar to the leg ulcers, stroke is particularly higher in the SCA and cases with higher WBC counts (118). Sickling-induced capillary endothelial damage, activations of WBC, PLT, and coagulation system, and hemolysis may terminate with chronic capillary endothelial inflammation, edema, and fibrosis (119). Probably, stroke may not have a macrovascular origin in the SCD, and diffuse capillary endothelial inflammation, edema, and fibrosis may be much more important. Infections, inflammations, medical or surgical emergencies, and emotional stresses may precipitate stroke by increasing basal metabolic rate and sickling. A significant reduction of stroke with hydroxyurea may also suggest that a significant proportion of cases is developed due to the increased WBC and PLT counts-induced exaggerated capillary inflammation and edema (120).

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is an autoimmune disorder of hemostasis characterized by low PLT counts in the absence of other causes. Depending on which age group is affected, ITP causes two distinct clinical syndromes: an acute form (resolving within two months) observed in children and a chronic form (persisting for longer than six months) in adults. Nevertheless, the pathogenesis of ITP is similar in both syndromes involving antibodies against various PLT surface antigens. Impaired production of the glycoprotein hormone, thrombopoietin, which is the stimulant for PLT production, may also be a contributing factor to the reduction of circulating PLT. The stimulus for auto-antibody production in ITP is probably abnormal T cell activity. Preliminary findings suggest that these T cells can be influenced by medications that target B cells, such as rituximab. Signs of ITP include the spontaneous formation of purpura and petechiae, particularly on extremities. In cases where PLT counts drop to extremely low levels (less than 5.000 per microliter), serious and potentially fatal complications including subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage may arise. In general, patients with ITP will rarely have life-threatening bleedings and the long-term prognosis of ITP is benign even in refractory cases (121). Most patients ultimately have lower, but stable PLT counts, which are still hemostatic for the patients (122). With rare exceptions, there is usually no need to treat based on PLT counts in ITP. PLT which have been found by antibodies are taken up by macrophages in the spleen, and so removal of the spleen reduces PLT destruction. Even though there is a consensus regarding the short-term efficacy of splenectomy, findings on its long-term efficacy and side-effects are controversial (123). Durable remission following splenectomy is achieved just in 60-80% of ITP cases (124). Additionally, this procedure is potentially risky due to increased risks of infections in the future due to the asplenism. The male to female ratio in the adult group varies from 1:1.2 to 1.7 in most age ranges and the median age of adults at the diagnosis is 56-60 years (125). Although, it was reported that ITP causes an approximately 60% higher rate of mortality compared to sex-and age-matched subjects without ITP, and 96% of reported ITP-related deaths were patients with the ages of 45 years and higher (126), we have just seen two mortile cases due to chronic ITP in our 25 years of experience up to now.

As a conclusion, hardened RBC-induced capillary endothelial damage initiating at birth terminates with multiorgan failures in much earlier ages in the SCD. Excess fat tissue may be much more important than smoking and alcohol for atherosclerosis, and CHD and stroke may be the terminal causes of death in both genders at the moment. Although the possibility of some severe bleedings in rare cases, we have just seen two mortile cases due to the chronic ITP in our 25 years of experience. Due to the well-known roles of PLT during the terminal atherosclerotic consequences, chronic ITP may even prolong the survival in human being in general.

References

-

Widlansky ME, Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, Vita JA. The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42(7): 1149-60.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet 2005; 365(9468): 1415-28.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Franklin SS, Barboza MG, Pio JR, Wong ND. Blood pressure categories, hypertensive subtypes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens 2006; 24(10): 2009-16.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002; 106(25): 3143-421.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydin LY, Aydin Y. Digital clubbing may be an indicator of systemic atherosclerosis even at microvascular level. HealthMED 2012; 6(12): 3977-81.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Anderson RN, Smith BL. Deaths: leading causes for 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2003; 52(9): 1-85.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Gokce C, Davran R, Akkucuk S, Ugur M, Oruc C. Mortal quintet of sickle cell diseases. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8(7): 11442-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med 1994; 330(23): 1639-44.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Yaprak M, Abyad A, Pocock L. Atherosclerotic background of hepatosteatosis in sickle cell diseases. World Family Med 2018; 16(3): 12-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Kaya H. Effect of sickle cell diseases on height and weight. Pak J Med Sci 2011; 27(2): 361-4.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Ayyildiz O. Hydroxyurea may prolong survival of sickle cell patients by decreasing frequency of painful crises. HealthMED 2013; 7(8): 2327-32.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Mankad VN, Williams JP, Harpen MD, Manci E, Longenecker G, Moore RB, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of bone marrow in sickle cell disease: clinical, hematologic, and pathologic correlations. Blood 1990; 75(1): 274-83.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Ayyildiz O. Clinical severity of sickle cell anemia alone and sickle cell diseases with thalassemias. HealthMED 2013; 7(7): 2028-33.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Fisher MR, Forfia PR, Chamera E, Housten-Harris T, Champion HC, Girgis RE, et al. Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography in the hemodynamic assessment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179(7): 615-21.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187(4): 347-65.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Davies SC, Luce PJ, Win AA, Riordan JF, Brozovic M. Acute chest syndrome in sickle-cell disease. Lancet 1984; 1(8367): 36-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Vandemergel X, Renneboog B. Prevalence, aetiologies and significance of clubbing in a department of general internal medicine. Eur J Intern Med 2008; 19(5): 325-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Schamroth L. Personal experience. S Afr Med J 1976; 50(9): 297-300.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW Jr. Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 1999; 341(15): 1097-105.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Gundogdu M. Smoking induced atherosclerosis in cancers. HealthMED 2012; 6(11): 3744-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

De Pergola G, Pannacciulli N. Coagulation and fibrinolysis abnormalities in obesity. J Endocrinol Invest 2002; 25(10): 899-904.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(2): 115-26.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: Potential adjunct for global risk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2001; 103(13): 1813-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cardiovascular risk: rationale for screening and primary prevention. Am J Cardiol 2003; 92(4B): 17-22.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA 1998; 279(18): 1477-82.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA 1999; 282(22): 2131-5.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Funahashi T, Nakamura T, Shimomura I, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Takahashi M, et al. Role of adipocytokines on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in visceral obesity. Intern Med 1999; 38(2): 202-6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Zhou B, Wu Y, Yang J, Li Y, Zhang H, Zhao L. Overweight is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease in Chinese populations. Obes Rev 2002; 3(3): 147-56.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Zhou BF. Effect of body mass index on all-cause mortality and incidence of cardiovascular diseases--report for meta-analysis of prospective studies open optimal cut-off points of body mass index in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2002; 15(3): 245-52.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Kaya H, Yalcin A, Kuvandik G. Prevalence of white coat hypertension in underweight and overweight subjects. Int Heart J 2007; 48(5): 605-13.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Heilbronn LK, Ravussin E. Calorie restriction and aging: review of the literature and implications for studies in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 78(3): 361-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Fodor JG, Tzerovska R, Dorner T, Rieder A. Do we diagnose and treat coronary heart disease differently in men and women? Wien Med Wochenschr 2004; 154(17-18): 423-5.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydin LY, Aydin Y. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be one of the terminal end points of metabolic syndrome. Pak J Med Sci 2012; 28(3): 376-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Kayabasi Y, Celik O, Sencan H, Abyad A, Pocock L. Smoking causes a moderate or severe inflammatory process in human body. Am J Biomed Sci & Res 2023; 7(6): 694-702.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Grunberg NE, Greenwood MR, Collins F, Epstein LH, Hatsukami D, Niaura R, et al. National working conference on smoking and body weight. Task Force 1: Mechanisms relevant to the relations between cigarette smoking and body weight. Health Psychol 1992; 11: 4-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Camci C, Nisa EK, Ersahin T, Atabay A, Alrawii I, Ture Y, Abyad A, Pocock L. Severity of sickle cell diseases restricts smoking. Ann Med Medical Res 2024; 7: 1074.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Walker JF, Collins LC, Rowell PP, Goldsmith LJ, Moffatt RJ, Stamford BA. The effect of smoking on energy expenditure and plasma catecholamine and nicotine levels during light physical activity. Nicotine Tob Res 1999; 1(4): 365-70.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK. Effects of three doses of transdermal nicotine on post-cessation eating, hunger and weight. J Subst Abuse 1997; 9: 151-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Miyata G, Meguid MM, Varma M, Fetissov SO, Kim HJ. Nicotine alters the usual reciprocity between meal size and meal number in female rat. Physiol Behav 2001; 74(1-2): 169-76.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Froom P, Melamed S, Benbassat J. Smoking cessation and weight gain. J Fam Pract 1998; 46(6): 460-4.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Kaya H, Gundogdu M. Gender differences in coronary heart disease in Turkey. Pak J Med Sci 2012; 28(1): 40-4.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Prescott E, Hippe M, Schnohr P, Hein HO, Vestbo J. Smoking and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men: longitudinal population study. BMJ 1998; 316(7137): 1043-7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Kabay S, Gulcan E. A physiologic events’ cascade, irritable bowel syndrome, may even terminate with urolithiasis. J Health Sci 2006; 52(4): 478-81.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Dede G, Yildirim Y, Salaz S, Abyad A, Pocock L. Smoking may even cause irritable bowel syndrome. World Family Med 2019; 17(3): 28-33.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Algin MC, Kaya H. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic gastritis, hemorrhoid, urolithiasis. Eurasian J Med 2009; 41(3): 158-61.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Kamimura D, Loprinzi PD, Wang W, Suzuki T, Butler KR, Mosley TH, et al. Physical activity is associated with reduced left ventricular mass in obese and hypertensive African Americans. Am J Hypertens 2017; 30(6): 617-23.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Bhatia LS, Curzen NP, Calder PC, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a new and important cardiovascular risk factor? Eur Heart J 2012; 33(10): 1190-1200.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Pacifico L, Nobili V, Anania C, Verdecchia P, Chiesa C. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(26): 3082-91.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Mawatari S, Uto H, Tsubouchi H. Chronic liver disease and arteriosclerosis. Nihon Rinsho 2011; 69(1): 153-7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Bugianesi E, Moscatiello S, Ciaravella MF, Marchesini G. Insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Pharm Des 2010; 16(17): 1941-51.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Mostafa A, Mohamed MK, Saeed M, Hasan A,Fontanet A, Godsland I, et al. Hepatitis C infection and clearance: impact on atherosclerosis and cardiometabolic risk factors. Gut 2010; 59(8): 1135-40.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Ayyildiz O, Gundogdu M, Aydin Y, Abyad A, Pocock L. Hyperlipoproteinemias may actually be acute phase reactants in the plasma. World Family Med 2018; 16(1): 7-10.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Parfrey NA, Moore W, Hutchins GM. Is pain crisis a cause of death in sickle cell disease? Am J Clin Pathol 1985; 84: 209-12.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Ayyildiz O, Gundogdu M. Hydroxyurea therapy and parameters of health in sickle cell patients. HealthMED 2014; 8(4): 451-6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Tonyali O, Yaprak M, Abyad A, Pocock L. Increased sexual performance of sickle cell patients with hydroxyurea. World Family Med 2019; 17(4): 28-33.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Atci N, Ayyildiz O, Muftuoglu OE, Pocock L. Red blood cell supports in severe clinical conditions in sickle cell diseases. World Family Med 2016; 14(5): 11-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Ayyildiz O, Gundogdu M. Red blood cell transfusions and survival of sickle cell patients. HealthMED 2013; 7(11): 2907-12.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Cayir S, Halici H, Sevinc A, Camci C, Abyad A, Pocock L. Red blood cell transfusions may have the strongest analgesic effect during acute painful crises in sickle cell diseases. Ann Clin Med Case Rep 2024; V13(12): 1-12.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Miller ST, Sleeper LA, Pegelow CH, Enos LE, Wang WC, Weiner SJ, et al. Prediction of adverse outcomes in children with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 83-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Balkaran B, Char G, Morris JS, Thomas PW, Serjeant BE, Serjeant GR. Stroke in a cohort of patients with homozygous sickle cell disease. J Pediatr 1992; 120: 360-6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Cole TB, Sprinkle RH, Smith SJ, Buchanan GR. Intravenous narcotic therapy for children with severe sickle cell pain crisis. Am J Dis Child 1986; 140: 1255-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Miller BA, Platt O, Hope S, Dover G, Nathan DG. Influence of hydroxyurea on fetal hemoglobin production in vitro. Blood 1987; 70(6): 1824-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Platt OS. Is there treatment for sickle cell anemia? N Engl J Med 1988; 319(22): 1479-80.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydogan F, Sevinc A, Camci C, Dilek I. Platelet and white blood cell counts in severity of sickle cell diseases. Pren Med Argent 2014; 100(1): 49-56.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Charache S. Mechanism of action of hydroxyurea in the management of sickle cell anemia in adults. Semin Hematol 1997; 34(3): 15-21.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Charache S, Barton FB, Moore RD, Terrin ML, Steinberg MH, Dover GJ, et al. Hydroxyurea and sickle cell anemia. Clinical utility of a myelosuppressive

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Steinberg MH, Barton F, Castro O, Pegelow CH, Ballas SK, Kutlar A, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA 2003; 289(13): 1645-51.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Lebensburger JD, Miller ST, Howard TH, Casella JF, Brown RC, Lu M, et al; BABY HUG Investigators. Influence of severity of anemia on clinical findings in infants with sickle cell anemia: analyses from the BABY HUG study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012; 59(4): 675-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Toghi H, Konno S, Tamura K, Kimura B, Kawano K. Effects of low-to-high doses of aspirin on platelet aggregability and metabolites of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin. Stroke 1992; 23(10): 1400-3.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009; 373(9678): 1849-60.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Algra AM, Rothwell PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies versus randomised trials. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(5): 518-27.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Macdonald S. Aspirin use to be banned in under 16 year olds. BMJ 2002; 325(7371): 988.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Schrör K. Aspirin and Reye syndrome: a review of the evidence. Paediatr Drugs 2007; 9(3): 195-204.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Pugliese A, Beltramo T, Torre D. Reye’s and Reye’s-like syndromes. Cell Biochem Funct 2008; 26(7): 741-6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Hurwitz ES. Reye’s syndrome. Epidemiol Rev 1989; 11: 249-53.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Meremikwu MM, Okomo U. Sickle cell disease. BMJ Clin Evid 2011; 2011: 2402.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Mohamed S, Fong CM, Ming YJ, Kori AN, Wahab SA, Ali ZM. Evaluation of an initiation regimen of warfarin for international normalized ratio target 2.0 to 3.0. J Pharm Technol 2021; 37(6): 286-92.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Chu MWA, Ruel M, Graeve A, Gerdisch MW, Ralph J, Damiano Jr RJ, Smith RL. Low-dose vs standard warfarin after mechanical mitral valve replacement: A randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2023; 115(4): 929-38.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Crowther MA, Douketis JD, Schnurr T, Steidl L, Mera V, Ultori C, et al. Oral vitamin K lowers the international normalized ratio more rapidly than subcutaneously vitamin K in the treatment of warfarin-associated coagulopathy. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137(4): 251-4.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Brown DG, Wilkerson EC, Love WE. A review of traditional and novel oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 72(3): 524-34.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM, Suissa S. Drug drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. CMAJ 2007; 177(4): 347-51.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Dahal K, Kunwar S, Rijal J, Schulman P, Lee J. Stroke, major bleeding, and mortality outcomes in warfarin users with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Chest 2016; 149(4): 951-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Chai-Adisaksopha C, Lorio A, Hillis C, Siegal D, Witt DM, Schulman S, et al. Warfarin resumption following anticoagulant-associated intracranial hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res 2017; 160: 97-104.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ferro JM, Coutinho JM, Dentali F, Kobayashi A, Alasheev A, Canhao P, et al. Safety and efficacy of dabigatran etexilate vs dose-adjusted warfarin in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2019; 76(12): 1457-65.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Meade TW. Low-dose warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischemic heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1990; 65(6): 7C-11C.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Singer DE, Hughes RA, Gress DR, Sheehan MA, Oertel LB, Maraventano SW, et al. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 1990; 323(22): 1505-11.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Levine M, Hirsh J, Gent M, Arnold A, Warr D, Falanya A, et al. Double-blind randomised trial of a very-low-dose warfarin for prevention of thromboembolism in stage IV breast cancer. Lancet 1994; 343(8902): 886-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2014; 383(9921): 955-62.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hill T, Hippisley-Cox J. Risks and benefits of direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in a real world setting: cohort study in primary care. BMJ 2018; 362: k2505.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009; 361(12): 1139-51.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Cayir S, Halici H, Sevinc A, Camci C, Abyad A, Pocock L. Terminal endpoints of systemic atherosclerotic processes in sickle cell diseases. World Family Med 2024; 22(5): 13-23.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Daglioglu MC, Halici H, Sevinc A, Camci C, Abyad A, Pocock L. Low-dose aspirin plus low-dose warfarin may be the standard treatment regimen in Buerger's disease. World Family Med 2024; 22(6): 22-35.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Erden ES, Aydin LY. Atherosclerotic background of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in sickle cell patients. HealthMED 2013; 7(2): 484-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Rennard SI, Drummond MB. Early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: definition, assessment, and prevention. Lancet 2015; 385(9979): 1778-88.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Schoepf D, Heun R. Alcohol dependence and physical comorbidity: Increased prevalence but reduced relevance of individual comorbidities for hospital-based mortality during a 12.5-year observation period in general hospital admissions in urban North-West England. Eur Psychiatry 2015; 30(4): 459-68.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo YF, Sharma G. Association of Psychological Disorders With 30-Day Readmission Rates in Patients With COPD. Chest 2016; 149(4): 905-15.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Mannino DM, Watt G, Hole D, Gillis C, Hart C, McConnachie A, et al. The natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2006; 27(3): 627-43.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Mapel DW, Hurley JS, Frost FJ, Petersen HV, Picchi MA, Coultas DB. Health care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A case-control study in a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160(17): 2653-58.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Enright PL, Manfreda J; Lung Health Study Research Group. Hospitalizations and mortality in the Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166(3): 333-9.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

McGarvey LP, John M, Anderson JA, Zvarich M, Wise RA; TORCH Clinical Endpoint Committee. Ascertainment of cause-specific mortality in COPD: operations of the TORCH Clinical Endpoint Committee. Thorax 2007; 62(5): 411-5.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Trent JT, Kirsner RS. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Adv Skin Wound Care 2004: 17(8); 410-6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Minniti CP, Eckman J, Sebastiani P, Steinberg MH, Ballas SK. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2010; 85(10): 831-3.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, Ballas SK, Hassell KL, James AH, et al. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA 2014; 312(10): 1033-48.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydogan F, Sevinc A, Camci C, Dilek I. Platelet and white blood cell counts in severity of sickle cell diseases. HealthMED 2014; 8(4): 477-82.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Myers KA, Farquhar DR. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have clubbing? JAMA 2001; 286(3): 341-7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Toovey OT, Eisenhauer HJ. A new hypothesis on the mechanism of digital clubbing secondary to pulmonary pathologies. Med Hypotheses 2010; 75(6): 511-3.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Nassiri AA, Hakemi MS, Asadzadeh R, Faizei AM, Alatab S, Miri R, et al. Differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors associated with maximum and mean carotid intima-media thickness among hemodialysis patients. Iran J Kidney Dis 2012; 6(3): 203-8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Gokce C, Sahan M, Hakimoglu S, Coskun M, Gozukara KH. Venous involvement in sickle cell diseases. Int J Clin Exp Med 2016; 9(6): 11950-7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Xia M, Guerra N, Sukhova GK, Yang K, Miller CK, Shi GP, et al. Immune activation resulting from NKG2D/ligand interaction promotes atherosclerosis. Circulation 2011; 124(25): 2933-43.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Hall JE, Henegar JR, Dwyer TM, Liu J, da Silva AA, Kuo JJ, et al. Is obesity a major cause of chronic kidney disease? Adv Ren Replace Ther 2004; 11(1): 41-54.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Nerpin E, Ingelsson E, Risérus U, Helmersson-Karlqvist J, Sundström J, Jobs E, et al. Association between glomerular filtration rate and endothelial function in an elderly community cohort. Atherosclerosis 2012; 224(1): 242-6.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Stengel B, Tarver-Carr ME, Powe NR, Eberhardt MS, Brancati FL. Lifestyle factors, obesity and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Epidemiology 2003; 14(4): 479-87.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Bonora E, Targher G. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 9(7): 372-81.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Cayir S, Halici H, Sevinc A, Camci C, Sencan H, Davran R, Abyad A, Pocock L. Acute chest syndrome and coronavirus disease may actually be genetically determined exaggerated immune response syndromes particularly in pulmonary capillaries. World Family Med 2024; 22(3): 6-16.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17(7): 2034-47.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Helvaci MR, Aydin Y, Aydin LY. Atherosclerotic background of chronic kidney disease in sickle cell patients. HealthMED 2013; 7(9): 2532-7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

DeBaun MR, Gordon M, McKinstry RC, Noetzel MJ, White DA, Sarnaik SA, et al. Controlled trial of transfusions for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(8): 699-710.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Majumdar S, Miller M, Khan M, Gordon C, Forsythe A, Smith MG, et al. Outcome of overt stroke in sickle cell anaemia, a single institution's experience. Br J Haematol 2014; 165(5): 707-13.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Kossorotoff M, Grevent D, de Montalembert M. Cerebral vasculopathy in pediatric sickle-cell anemia. Arch Pediatr 2014; 21(4): 404-14.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med 1995; 332(20): 1317-22.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Stasi R, Stipa E, Masi M, Cecconi M, Scimò MT, Oliva F, et al. Long-term observation of 208 adults with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med 1995; 98(5): 436-42.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

McMillan R, Durette C. Long-term outcomes in adults with chronic ITP after splenectomy failure. Blood 2004; 104(4): 956-60.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Vianelli N, Galli M, de Vivo A, Intermesoli T, Giannini B, Mazzucconi MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of splenectomy in immune thrombocytopenic purpura: long-term results of 402 cases. Haematologica 2005; 90(1): 72-7.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Chaturvedi S, Arnold DM, McCrae KR. Splenectomy for immune thrombocytopenia: down but not out. Blood 2018; 131(11): 1172-82.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Cines DB, Bussel JB. How I treat idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Blood 2005; 106(7): 2244-51.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar -

Schoonen WM, Kucera G, Coalson J, Li L, Rutstein M, Mowat F, et al. Epidemiology of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in the General Practice Research Database. Br J Haematol 2009; 145(2): 235-44.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar